While it is simple to identify how women and men are differently impacted by transportation, there is a lack of focus on good practices where gender-aware principles have been successful within transportation planning and implementation.

While it is simple to identify how women and men are differently impacted by transportation, there is a lack of focus on good practices where gender-aware principles have been successful within transportation planning and implementation.

By Gillian Ertel

One of the most important principles is how anti-sexual harassment campaigns have been mainstreamed by transportation authorities into everyday operations. London, Colombia, Mexico, and France have active campaigns that call attention to understanding how women’s experiences in cities are vital to fully grasp the problem of sexual harassment in public transport.

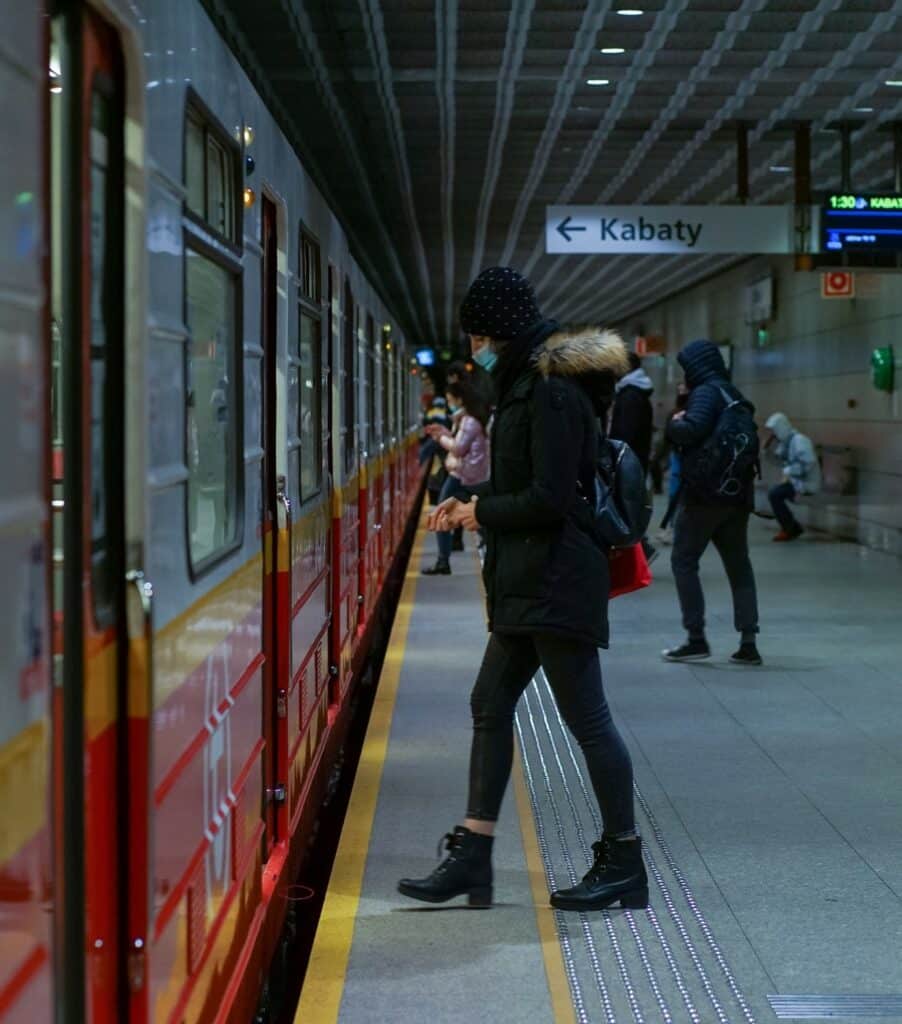

Access to safe transportation is the lifeline for women’s access to employment, education, and social opportunities. Reduction of violence and sexual harassment of women is vital, as women face a greater risk of violence and harassment than men (Nakefeero, 2016). Calling attention to successful campaigns implemented by governments, transport authorities, or other stakeholders on how to reduce sexual harassment through public transportation operations creates an outline for best practices.

Recently, violence and specifically sexual harassment in public spaces (such as transport) have gained attention- due to women being major users of public transport and active transport. According to The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), up to 55% of women within the European Union had experienced sexual harassment in public transport (FRA, 2014). Within less developed regions, these numbers appear higher. Within Mexico, over 64% of women living in Mexico stated they have experienced some form of harassment on public transport (United Nations, 2020.). One reason for this is that women in these regions are far more reliant on public transport, therefore leading to higher rates of overall transit users. When public transportation is unsafe for women, a transport disadvantage occurs and creates social inequalities based on gender. Harassment within public transport has a massive impact on daily life- not just their professional lives, but how women dress, their social endeavors, amongst financial losses due to using other types of transport. For example, just within France, 48% of women changed the way they dressed, 34% said they used other types of transport, and 9% said they would not travel alone (F. R. A. N. C. E, 2015). It is vital to observe these examples of sexual harassment campaigns to help identify promising best practices to create safe, gender-responsive public transport planning and policies.

In October 2021, the city of London implemented a Zero-Tolerance campaign to end sexual harassment on London transport systems. Sexual harassment is a form of violence, most often directed against women and girls in public places. London is challenging the normalization and acceptance of these behaviors, as Transport for London states, it will take a zero-tolerance approach to any form of unwanted sexual behavior on the transport systems (Transport for London, 2021). Victims and those who witnessed incidents are urged to report so that there can be immediate action taken against offenders. Harassment tends to be underreported, and one reason for this is how incorrectly conceptualized the term has been. Transport for London addresses this issue by highlighting behaviors that are common examples of sexual harassment that are designed to boost reporting through creating awareness of what to look for. These behaviors include:

The campaign builds on efforts to tackle sexual harassment through Project Guardian. While London already has an award-winning Report it to Stop it Campaign, the newly implanted communication campaign intends to move it one step forward to ensure women, girls, and the Gender Diverse feel safe as they travel. The new campaign includes staff wearing body cameras while receiving extensive training on how to deal with these behaviors, along with an extensive CCTV network (Transport for London, 2021). There will be over 2,500 community support officers (including police) patrolling the transportation systems, while also carrying out targeted policing and investigation to those committing acts of sexual harassment (Transport for London, 2021). Transport for London has additionally made toolkits on how to be an active bystander, how to report, what to report, and information sheets on why women do not report. This not only gives victims an outlet for justice for the crime committed against them, but it also gives the public an opportunity to step in and make women and girls feel safe while traveling.

According to a study done in 2020, most women in Bogota were unaware of any initiatives aimed at reducing sexual harassment in public spaces or transport (Quinones, 2020). Being said, the initiatives that have been implemented have not been widely communicated or have not had much impact.

However, there are initiatives in place intended to communicate responsiveness to sexual harassment in transport systems that did not receive a positive response. For one, a pilot project of segregated sections based on gender, or even separate busses- which ended up not being very successful and therefore lead to a proposal for preferential seats for women. Both these pilot proposals were focused on Transmilenio- yet both were not successful in reducing harassment (Quinones, 2020). According to a study done in 2020, one survey respondent agreed that segregating men and women was not a proper solution:

Here they haven’t really done anything, and they have done the worst, which is that pink seat and pink TransMilenio thing, that the only thing that does is separate and worsen the problem. It’s like, ́we can’t put them together, a man can’t learn how to behave, so we need to be separated’. That is really mediocre. (Quinones, 2020)-

Due to the lack of improvement, and overall dissatisfaction with the segregated sections, the pilot project was discontinued. Beyond the lack of success, it can be argued that implementing segregated spaces- opposite as intended- rather reinforces normalization of harassment, and ultimately feeds the narrative.

Women in Mexico have similar thoughts and experiences in regard to their safety in public transportation systems. According to one study, more than 64% of women living in Mexico have experienced some form of harassment on public transport. Therefore, the government appropriately responded by implementing the “Viajemos seguras” (“Let’s travel safe”) initiative, with the intent of making transport sage for women. As public transport is quite prominent in Mexico- 15.7 million people use public transportation a day, there need to be measures in place to ensure safety for all (United Nations, 2020). The initiative is seen as pioneering due to the multimodal aspects of the initiative- focusing on the bus, subway systems, and taxis.

The campaign includes offices within the transport system specific to reporting violence, training security service providers, and communication campaigns highlighting what behaviors are considered inappropriate. This is a multilateral project, with both state agencies and transport systems cooperating, that integrated connections of outskirt areas of Mexico to other neighborhoods to ensure safe access for all.

In a study done in 2016, 87% of women in France stated they have experienced sexual harassment in public transportation, with 89% stating witnesses were present and did not react (Île-de-france, n.d.). In response, a vast communication campaign across the public transport sector worked to never minimize sexual harassment on transport. The campaign was launched in 2018, and sought to educate all public transport users about harassment and attempted to encourage users to report acts they experience or witness.

This campaign was aimed to raise awareness on the prevalence of how often sexual harassment occurs in public transport, but beyond that, inform the public of the legal framework in place that protects against sexual harassment, and tips for how to react. This included:

Improving the situation for women on public transit varies for the region on the globe one resides in. As previously stated, the segregation of genders to reduce sexual harassment sends the wrong message to both perpetrators and victims of sexual harassment. Based on the prior examples of best practice, there are a few key recommendations on how to properly communicate anti-sexual harassment campaigns for transit systems to ensure an inclusive mobility system:

FRA (2014). “Violence against women: an EU-wide survey. Main results report”. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. 3 February 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

F. R. A. N. C. E. (2015, November 10). French campaign targets sexual harassment on public transport. France 24. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.france24.com/en/20151110-france-tackles-sexual-harassment-public-transport

Île-de-france – public transport anti-harassment campaign. (n.d.). Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://charter-equality.eu/exemple-de-bonnes-pratiques/ile-de-france-public-transport-anti-harassment-campaign.html

Nakefeero, A. (2016). Freedom to Move. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://actionaid.org/publications/2016/freedom-move#downloads.

Quinones, L. M. (2020). Sexual harassment in public transport in Bogotá. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 139, 54-69. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2020.06.018

Transport for London | Every Journey Matters. (2021, October). New campaign launches to stamp out sexual harassment on public transport. Transport for London. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2021/october/new-campaign-launches-to-stamp-out-sexual-harassment-on-public-transport

United Nations. (n.d.). Women’s access to safe transport. Women’s access to safe transport. Retrieved January 10, 2022, from https://www.endvawnow.org/es/articles/1991-womens-access-to-safe-transport.html

Gardner, N., Cui, J. & E. Coiacetto (2017): Harassment on public transport and its impacts on women’s travel behaviour, Australian Planner, 54:1, 8-15, DOI: 10.1080/07293682.2017.1299189

Neupane, G. & M. Chesney-Lind (2014): Violence against women on public transport in Nepal: sexual harassment and the spatial expression of male privilege, International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 38:1, 23-38, DOI: 10.1080/01924036.2013.794556

Orozco-Fontalvo, M., Soto, J., Arévalo, A. & O. Oviedo-Trespalacios (2019): W omen’s perceived risk of sexual harassment in a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system: The case of Barranquilla, Colombia, Jounral of Transport & Health, 14, 100598, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2019.100598.

Solymosi, R., Cella, K. & A. Newton (2018): Did they report it to stop it? A realist evaluation of the effect of an advertising campaign on victims’ willingness to report unwanted sexual behaviour. Secur J 31, 570–590, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-017-0117-y.

Tudela Rivadeneryra, A., Lopez Dodero, A., Ray Mehndiratta, S., Bianchi Alves, B. & E. Deaking (2015): Reducing Gender-Based Violence in Public Transportation: Strategy Design for Mexico City, Mexico, of the Transportation Research Board, 1, 187-194. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3141/2531-22.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information