As an increasing number of organizations commit to gender-sensitive policies, adopting comprehensive Feminist Development Policies will facilitate the development of locally driven transport solutions and innovations that will improve the transport experience for women and girls and move cities towards a sustainable, just transition.

Feminist Development Policy and the Just Transition: Complimenting forces for gender equitable transport

The last decades have brought about a growing recognition of how important addressing gender disparities around the world is. National governments in some countries such as those in Canada and Germany are aiming for cabinets with gender parity. High-profile public and private organisations are increasing the representation of women at senior levels, like Bogotá, Colombia where women hold a high number of leadership positions. These steps, among others, provide opportunities for those who identify as women i to enjoy greater access, comfort, and safety in their daily lives. As these conversations increase, so do the number of governments and global organisations prioritising gender–specifically feminist–related policies. Still, this can go further, with just eight countries having enacted dedicated Feminist Foreign Policies (FFP)as of July 2022;

- Sweden (2014)

- Canada (2017)

- France (2019)

- Mexico (2020)

- Spain (2021)

- Luxembourg (2021)

- Germany (2021)

- Chile (2021)ii

While this is a promising move in the right direction, defining what this looks like on a global scale is complex and highly influenced by individual perceptions of what FFP should achieve.

Defining feminism depends a lot on our individual experiences, influenced by factors such as geographic location, age, income, race, and level of education, and, in many parts of the world, also shaped by anti-racist and anti-colonialist thinking, particularly in countries with a history of colonialism, slavery, and race-based policies.

Regardless of the definition, with more nations developing FFPs and Feminist Development Policies (FDPs) a positive impact from the implementation of these policies is being seen. FDPs can help move more nations into greater gender equity by providing funding and initiative linked to a commitment. When combined, this can potentially become a mechanism to serve as a force for good.

Germany’s commitment to Feminist Development Policy

Germany has been leading the way in this area. The Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (BMZ – Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development) is committed to an FDP focused on the following three key goals:iii

- Feminist development policy is centred around all people and tackles the root causes of injustice such as power relations between genders, social norms, and role models.

- Feminist development policy enhances equality for people of all genders and thus is to the advantage of the whole of society – including men.

- Feminist development policy is a powerful approach to take sustainable development forward and assert human rights worldwide, regardless of gender and any other personal traits.

In March 2023, the BMZ further announced a commitment to a more strategic approach which states the following:

»The BMZ will double the share of newly committed project funds for measures with the primary goal of gender equity to 8% by 2025 and increase the share of funds by 85% for those projects where it is the secondary objective. The expansion of focused projects is to take place across all regions and sectors in close coordination with partners and taking into account the country context.«

Each of the above goals are linked to the fact that globally, women do not enjoy the same level of advantages as their male counterparts. Basic human rights to safety and access are often undermined by continuous male-dominated thinking and planning that does not understand or reflect women’s needs. Therefore, FDPs aim to bridge these injustices and work to dismantle harmful power structures.

There are countless fields where FDPs are implemented to address these deep structural inequities, but for the purposes of this essay, I will focus on the connection between FDPs and sustainable and just transport systems. Just transitions aim to create a more sustainable economy that is equitable and accessible for all, ensuring that no group benefits more than another.

What is a development policy?

A development policy encompasses all political, economic, and social measures to help improve living conditions in developing countries in a sustainable way. The relationship can be bilateral (cooperation between two countries) or multilateral (cooperation between three or more countries).

Feminism and the climate change nexus

Transportation, namely the modes we use to move in cities, is directly linked to our impact on the climate. Over a century of relying on internal combustion engines to move people and goods has had damaging effects on our climate. As of 2018, the transport sector contributes 24% of global CO2 emissions, with road transport being the largest contributor (about 75%iv). At the same time, women’s transport behaviour and modal choices are much more sustainable than their male counterparts, whether by choice or by necessity. In surveys and data collection efforts, walking, cycling, or public transport are consistently shown to be the more popular transport choice for womenv. Additionally, women are more likely to choose a more climate-friendly transport optionvi.

Based on this, this essay aims to address three core questions:

- Why are FDP’s in transport necessary to address the climate crisis?

- What challenges exist in their successful implementation?

- How FDP funding can help apply feminist perspectives to the transport sector, particularly when it values a combination of international knowledge and local best practice?

Expert-interviews, academic research, and two case studies are combined that demonstrate the applicability and importance of FDPs to improve the quality and access to mobility for women. The case studies highlighted are:

- The SMART-SUT Programme in India, a partnership between India’s Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (MOHUA) and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH (German Society for International Cooperation)

- Safetipin App, co-founded by Dr. Kalpana Viswanath and Ashish Basu and supported by dozens of international Governmental and NGO partners, among others.

The fact is that women inherently experience the world differently. As a non-homogenous group, the intersectionality of age, race, level of education, employment, family and relationships, sexual and gender orientation, etc., all result in diverse transport behaviours. Understanding this and valuing it to enable greater mobility equity is a key ingredient to moving toward a sustainable future that benefits everyone. FDPs will play an important role here, but it is vital that they address the nuance of perspectives and acknowledge the existing power structures. They can make a meaningful impact on programming, policies, and budgeting, but must be approached from a place of open-mindedness and a desire to exchange knowledge. Assuming what works for one group–in this case, men–will work for everyone has got us to this critically dangerous point in history. This must change if we are ever to realize a more equitable and sustainable future. FDPs are one step in the right direction.

What is “just transport” and the “Just Transition”?

The just transition is understood and creating a more sustainable economy that is also fairly distributed and accessible, so no one group benefits from the opportunities created for work more than another. As an extension of that, just transport is the expansion and support for sustainable transport options that are equally accessible to everyone regardless of age, gender, race, socio-economic background, or ability.

Making the Case for Feminist Development Policies

Mention the word feminist and it is met, time and again, with the question: Why does an approach need to be ‘feminist’? Doesn’t that leave out the experiences of the other 50%? Looking past the counterargument that historically, approaches have only favoured that other-male-50%, research is showing that when we take a feminist lens to policy development, it becomes more inclusive. In May of 2022, German Minister of Foreign Affairs Annalena Baerbock stressed that feminism, in fact, addresses societal needs as a nuanced whole.

Feminist foreign policy isn’t about exclusion, it’s about inclusion. It’s not about hearing fewer voices, but more voices. It’s about hearing all the voices of society. Feminist foreign policy is not a “women’s issue”. Because we all benefit from it! If half the population does not have the opportunity for equal participation, no society can realize its full potential. And if half the world’s population is excluded, we cannot achieve lasting peace and security.vii

Minister Baerbock’s statement is guided by the “three Rs” used to design Sweden’s FFP and stands for Rights, Representation, and Resources. To reflect the need for a more non-Western perspective on ‘feminism’ and to acknowledge the importance of diversity and intersectionality, the 3Rs has been expanded to 3RS + D, where D represents enhanced diversity.

This is probably best defined by Lyric Thompson and Rachel Clement in their paper, Defining Feminist Foreign Policy (2019) as:

A Feminist Foreign Policy is the policy of a state that defines its interactions with other states and movements in a manner that prioritizes gender equality and enshrines the human rights of women and other traditionally marginalized groups, allocates significant resources to achieve that vision, and seeks through its implementation to disrupt patriarchal and male-dominated power structures across all of its levers of influence (aid, trade, defense, and diplomacy), informed by the voices of feminist activists, groups, and movements.viii

As an extension of FFPs, FDP is an intention from global actors to create policies that take a more collaborative effort in addressing inequities and the rights of women. This involves working directly with the countries that are engaged to provide resources where needed, all while ensuring the right people are represented at the table. In her paper, The Value of a Feminist Foreign Policy, author Shannon Zimmerman lays out four recommendations to guide the development of an effective FFP that can be naturally extended to developing an FDP:

Include women at all levels:

Women and non-gender-binary participants need to be an equal part of policymaking at all levels, not just as advisors but as leaders and substantive content contributors.

Address structural power imbalances:

Take ownership of the negative impact that its foreign policy actions have had on its neighboring states and then strive to ensure that these biased, dated policies are not used as precedent for current policies.

Foster cooperative policies and structures:

Look beyond the needs of the state to address the needs of individuals, particularly marginalized groups.

A comprehensive approach to foreign policy:

A strong feminist foreign policy would reject policy built on a nationalized military-based security premised on states’ rights and a patriarchal, rules-based order.ix

As a structure for change, FDPs provide organizations with the ability to support local efforts while addressing root causes of gender inequality on a global scale. Working collaboratively with local actors increases the potential for meaningful projects, programmes, and policies to enable greater gender equity to succeed as they become exposed to the challenges experienced directly from the people most impacted. This also allows some of the overarching issues of racism, classism, ableism, and colonialism to be addressed. An implementation of FDP can offer a potential funding mechanism to states with fewer resources to enact impactful policies, many of which would be difficult to achieve on their own. Applying the 3 Rs + D approach would allow us to address actual needs and experiences of women and to tailor them to according to local conditions.

The three Rs

Rights

Feminist development policy is committed to eliminating discriminatory laws and achieving legal empowerment and equal opportunities for women, girls and LGBTQI+ persons in all areas of life.

Resources

There needs to be justice in access to resources. Feminist development policy, too, depends on adequate resources to be successful.

Representation

All groups that have so far been insufficiently represented are to be involved in policy decision-making processes and enabled to exert influence at all levels.

Source: BMZ

Feminist Development Policy and the Just Transition

What is the relationship between more gender-sensitive, feminist development policies and achieving the just transition to a more sustainable future? It is well recognized in many places that a shift to sustainable transport on a global scale will play a large role in addressing the ongoing climate crisis. It is critical at this point in history for development projects and programmes to enable countries around the world to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals and address the climate crisis. Gender-focused transport projects provide an excellent starting point because we know that women’s mobility patterns are often more sustainable in nature, leaning heavily towards walking, cycling, and public transport. Policies focused on women are integral to achieving a more climate resilient transport system and increasing women-led initiatives.

Claudia Adriazola-Steil is Senior Associate at the World Resources Institute (WRI), a global research organization that works with governments, businesses, multilateral institutions, and civil society groups. For Adriazola-Steil, funding through mechanisms like FDPs needs to be more of a priority from philanthropic organisations and development banks.

Equity cannot happen when it is dependent on a few passionate advocates and limited funding. We know that it is necessary to invest in walking and cycling, but if the political and financial support is not there, it’s not going to happen. Many organizations recognize the importance of ensuring accessibility for walking and cycling, but they struggle to turn that (financial) action into reality. If it is going to be a transition, the transition has to also help women have fairer transport.

Many local, regional, and national governments are working with stretched budgets, but the scale of the just transition is so large in scope that knowing where to start can be overwhelming. Additionally, existing power structures or priorities may mean governments don’t even realise the imperative for these projects. Therefore, the role of FDPs, particularly in relation to transport focused projects, is essential to the decarbonization debate, as it plays a role in promoting initiatives and programmes aimed at gender-sensitive transport. Adriazola-Steil notes that requests from the bottom-up are often not there. “In terms of road safety, for example, there is some demand, but it tends to be misinformed due to lack of knowledge. It would be important to get the middle ground.” Development banks and global NGOs have the money and the research to help realise this middle ground, especially considering the varied contexts across geographic locations and cultures.

The success of FDPs and the projects on the ground requires a balance between understanding the desires of the people and providing technical, ‘best practice’ knowledge. “It is important to be respectful, and not to approach with a sense of arrogance,” Adriazola-Steil notes. “Agendas like sustainable transport and gender are very progressive, and sometimes haven’t yet taken root in some parts of the world.” Still, feminist development policies, and ultimately more feminist cities, are the path forward to addressing this climate crisis. Adriazola-Steil emphasizes:

Women have more sustainable transport patterns: We take public transport even if it’s uncomfortable, we walk even if it is dangerous, we want lower speeds because our need is not to be rushing, so we are a huge part of the solutions.

In Cities for Life, Corburn notes that an important aspect of climate justice is meaningful participation of the most vulnerable in the measurement of risk, risk-mitigation strategies, and monitoring progressx. Monitoring the success of projects and using the available data collected through a variety of sources will be valuable in showing the impact of FDPs, identifying areas of growth, and ultimately providing more equitable and resilient transport. “Measure the needs, and then measure change,” says Adriazola-Steil. “If you’re not measuring it won’t happen.”

In Cities for Life, Corburn notes that an important aspect of climate justice is meaningful participation of the most vulnerable in the measurement of risk, risk-mitigation strategies, and monitoring progress.

The Challenge: Separating positive change from personal gain

For all the good an effective FDP can provide, many run the risk of repeating past mistakes. There is a tendency in foreign policies to share and implement knowledge with the top-down approach, assuming that best decisions can only be achieved through experts’ opinions.

This approach ignores the fact that locals are the experts of their experience, and combining their knowledge would benefit the development of meaningful, sustainable solutions. Therefore, those creating FDPs first need to acknowledge and address the structural inequities that have led to the current gender imbalance. FDPs and the larger framework of FFPs are not working from a fixed understanding of what feminism is and this creates both opportunities and challenges as the feminist agenda continues to develop.

In the paper The Growth of Feminist (?) Foreign Policy (2020), author Jennifer Thomson notes for some nations, policies may focus more on economic gains for their countries and/or organizations implementing them. At the same time, less attention is given to the structural changes required to address issues around patriarchal planning standards, as well as the experiences of marginalised groups and the ongoing impacts of colonisation, heteronormativity, racism, imperialism, and militarism. Due to the lack of a universally accepted definition of feminism, feminist development policies can be criticized for being economically driven. “This renders development and policy work along the lines of capitalist business logic, rather than understanding of rights, equality and structural problems.”xi

Dr. Kalpana Viswanath, co-founder of Safetipin, notes, “If we truly want transformation in our cities, we have to move beyond a piecemeal approach to change.” However, she goes on to explain that at a policy level, feminist policy, especially in terms of urban policy, is grounded in two important principles:

The work of care

Feminist policy recognizes the work of care, and the care economy is the basis upon which any urban system functions. It is often invisible, operating under the assumption that the work will be completed regardless of existing systems. This invisible system enables for the entire urban structure to function as it does. When that thinking is unpacked, it becomes possible to challenge the fact that they are largely born by women, and this recognition may lead to new ideas for how to make it more equitable.

The impact of gender-based violence

A feminist policy recognizes how much gender-based violence impacts the lives of women and other marginalized groups in terms of their ability to access opportunities. Women’s lives are shaped by violence and fear of violence in many ways that are again invisible and may not be experienced every single day, but they must be acknowledged and be planned for how they deny women equality.

Addressing these challenges requires first stepping into a place of humility, a recognition that to actually address the root causes of inequity, those who provide development resources cannot look only at the return on individual investment to solve the problem. To address the intersectionality of daily lives, feminist policies must also recognize the diversity of women’s experiences and needs that aren’t being addressed. As women are predominantly the main caregivers, improvements that benefit women would benefit their children, the elderly, marginalized groups, as well as men who have diverse needs. Taking a feminist lens on this issue would benefit everyone, from improved safety, access, to greater opportunities. Support for these projects is support for an improved collective experience, even when no direct gain is apparent.

We had the chance to interview Dr. Kalpana Viswanath about her perspective on feminist policies in transport for our book publication “Remarkable Feminist Voices in Transport 2023”. Read her interview below!

The fifth annual Remarkable Women edition aims to showcase the power of diverse visions for feminist transport policy. A public call for “Feminist Voices in Transport” resulting in over 80 nominations from over 20 countries. Download the book below!

Need to work with locals – Taking a trauma informed and healing-centred approach

When ensuring that the solution-driven programs do not come from a place of personal gain but one that values diversity, it is incredibly valuable to learn from the local experiences to guide the development of programmes. This starts with addressing the root causes of the inequities, however this can bring pre-existing trauma for an individual or group to the surface. In many cases, states seeking to implement an FDP are often those whose policies have affected and harmed people. Therefore, meaningful solutions need to first acknowledge this, make space for listening and understanding, and then work together with local players on collaborative solutions.

In Cities for Life, Jason Corburn refers to this step as ‘Coproduction’xii. Corburn refers to an approach employed in Medellín, Colombia called ‘social urbanism’ which invites and encourages residents to define their needs as a means to co-design solutionsxiii. This approach, when employed meaningfully, can result in a project, programme, or policy that presents solutions that actually address the local contexts. This is especially important when discussing policies and programmes implemented by foreign entities with external experiences and knowledge.

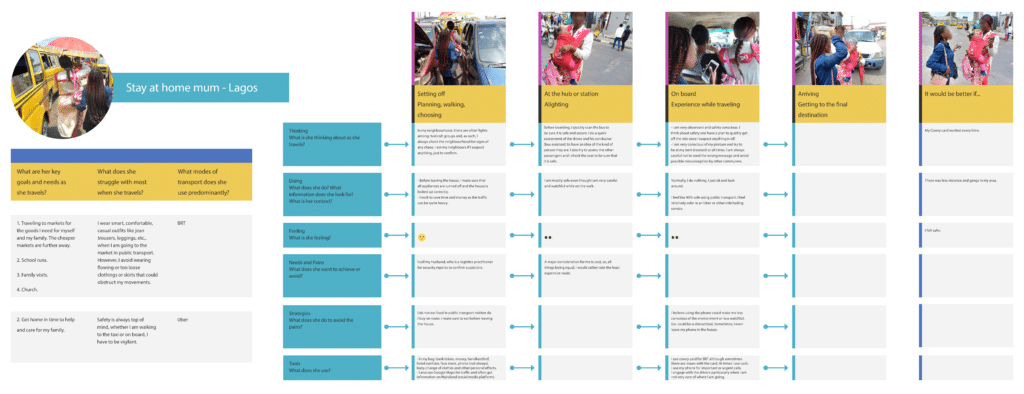

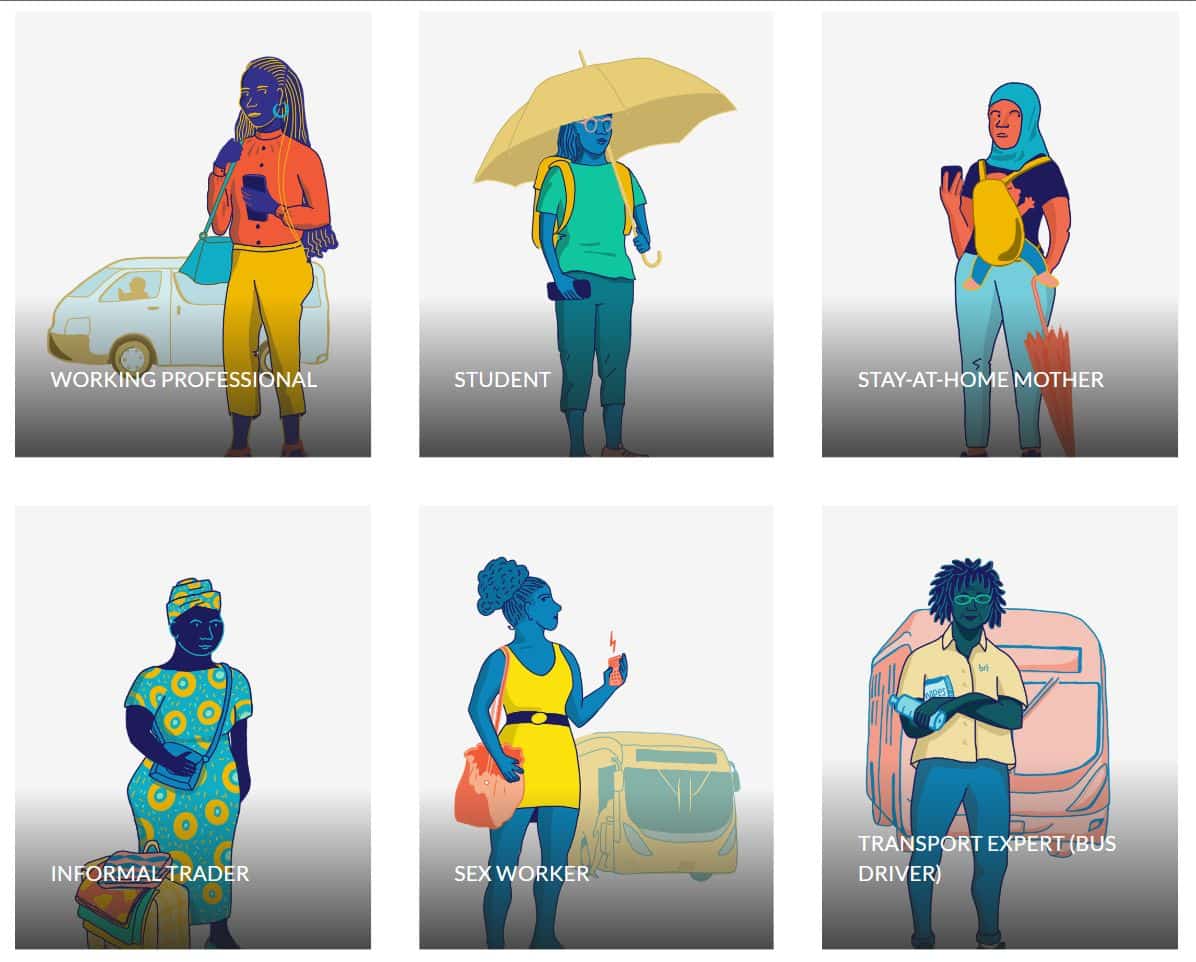

Coproduction and social urbanism are both built on the understanding that, while inequalities experienced by people globally may have similar root causes, solutions can and often are contextually different. This fact was reinforced in the recent gender data gap study executed by Where Is My Transport in three African cities: Nairobi, Kenya, Lagos, Nigeria, and Gauteng, South Africa. While many of the reasons for dissatisfaction (e.g., cost, level of choice, fear of harassment) with public transport were the same–the potential solutions that the local women provided during workshops and ride-alongs varied from city to city. This could only have been understood by speaking directly to the women impacted.xiv

If local representation and involvement has the power to create successful programmes, the question could be asked: Do development banks, global NGOs, and other actors, particularly those established in countries in the Global North, have a responsibility to support feminist development in the Global South? It could be argued that the people best suited to develop solutions are the states themselves.

However, as noted above, existing power structures may prevent feminist thinking and advancement in gender equity. Dr. Viswanath insists that external funding has a place in local development.

»I think everyone has a responsibility. However, it cannot come in a way that says, ‘This is feminist development policy, and this is how you must include it.’ It must be allowed to arise locally because it is contextual.«

Dr. Viswanath notes that at a local level, available budgets are stretched across many priorities. To address global gender inequities, external funding can provide an avenue for realising programmes and projects that otherwise would struggle to succeed. “What donors and others can do is recognize the fact that it’s contextual and allow for cross learning,” says Dr. Viswanath. “It’s not always the Global North bringing the best examples to the Global South, it can also be the other way around.”

The benefit, according to Dr. Viswanath, is that nowadays there is more recognition that learning and development are not one way, and donors and bilaterals/multilaterals can play a stronger role in that arena. This includes both being aware and respectful of it, as well as promoting it.

For example, Vienna, Austria is continually presented as a symbol of success in gender-equitable that should be aspired to. However, to a city like Delhi, the contextual differences between the two geographies may be difficult to overcome. Perhaps more relatable would be to look to the city of Bogotá, Colombia. The city of 8-million people is focused on addressing the social mobility needs of women through investments in programmes like the Manzana del Cuidado (Care Blocks), that provide centres for caring for dependents while women in low-income areas learn and develop skills to increase employment and entrepreneurship potential. Additionally, La Rolita is a public-private transport service provider currently training and employing 60% women as operators, administrators, and management.

»When you give the example of Bogotá, another city in the south becomes much more relatable,« Dr. Viswanath states. »Change is complex, and you must recognize social change is also complex. It’s not a simple A to B – recognizing that complexity is what is needed.«

Coproduction

“Coproduction involves identification of stressors and challenges from the person experiencing it, and not someone outside.”

Decoding women’s transport experiences

Discover the transport experience of women from Nairobi, Lagos, and Gauteng by user group!

Bridging the gender data gap in transport

Based on learnings from our project on the gender data gap in transport, we developed a beautiful poster featuring six principles for good practce. You can download it as one, or as 6 individual pages with an image of each princliple. Feel free to share!

Case Study 1: SMART-SUT Project, India

The Integrated Sustainable Urban Transport Systems for Smart Cities (SMART-SUT) project in India is jointly implemented by GIZ India and the Indian Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA), and it is commissioned by the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). It is part of the Indo-German Green Urban Mobility Partnership (GUMP) between MoHUA and BMZ. The technical assistance projects of GIZ are guided by an agreement where both parties define on the project’s scope, its desired outcomes, and its indicators (guidelines) and then align them with the proposed project activities. While initiated at the national level, the SMART-SUT project supported three states – Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Kerala – and several cities which mainly include Bhubaneswar and its surroundings, Coimbatore, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram.

The activities defined for this project included city bus service improvements, non-motorized transport (NMT) improvements, inclusion, road safety, low carbon mobility, and capacity building. While gender inclusion was not an explicit indicator of the project, the team nevertheless tried to include this aspect wherever possible. Based on available research and data, access for women was identified as a barrier, both in terms of reaching education and employment, also within transport agencies. As a result, SMART-SUT supported the cities to address some of these barriers and improve social inclusion. The activities were identified based on discussions with the city and state.

In Bhubaneswar, the public transport agency Capital Region Urban Transport (CRUT), wanted to initiate a low carbon emission first and last mile feeder to the city bus service, with specific focus on social inclusion. As a result, SMART-SUT supported CRUT in procuring 80 electric-rickshaws, which were driven by women, transgender, and HIV positive people. Further, training modules were also curated which would not only equip them with new skills and employment opportunities but would help address the safety concerns experienced by women users. Through the training programme, participants were trained to operate e-rickshaws, while also developing financial literacy skills, as well as how to interact with customers. While it is still too early to measure the long-term effects of the project, the impact of this project is significant and CRUT has won the United Nations Public Service Award 2022 for it.

It is one-of-a-kind initiative, focussing not only on women empowerment, but also on inclusion of other vulnerable groups in the transport sector. It also presents an opportunity to build intersectionality into social and gender inclusion programming. Furthermore, gender inclusion in planning and implementation stages can make transport systems more gender inclusive

Additional joint activities in Bhubaneswar further reinforced a more gender-sensitive approach. These included gender-sensitivity training for transport staff including operators, ticketing staff, local planners, and engineers, as well as addressing infrastructural changes including seating, lighting, and ticketing services. In Bhubaneswar, the approach was much more gender-explicit, with activities that will have both internal and external impact in the long-term.

The SMART-SUT also supported the city of Kochi, where a cycle training was delivered that helped to empower more than 700 women with the skills to use cycles for their personal mobility. While cycling skills alone will not address the necessary upgrades needed to build safer infrastructure, it does however provide these women with the choice to cycle, and potentially opens other avenues not just to reach employment but also greater access to opportunities through their newfound skills. A survey of the women trained has shown 34% have shifted to cycling for their commute, and 1 out of 4 unemployed women trained under the programme found a job after the training.

Looking ahead, the team hopes that these initial initiatives will be expanded to other Indian regions and cities to improve the availability of sustainable urban transport options and more gender inclusive programming, tailored according to the local context. SMART-SUT is an example of how local governments and groups can work together to not only fund projects but also to come up with locally contextual solutions to achieve outcomes that address existing power structures and promote equity in the community. The SMART-SUT project ended in 2022 and has been followed by the Sustainable Urban Mobility – Air quality, Climate Action, Accessibility (SUM-ACA) project.

Case Study 2: Safetipin – Global

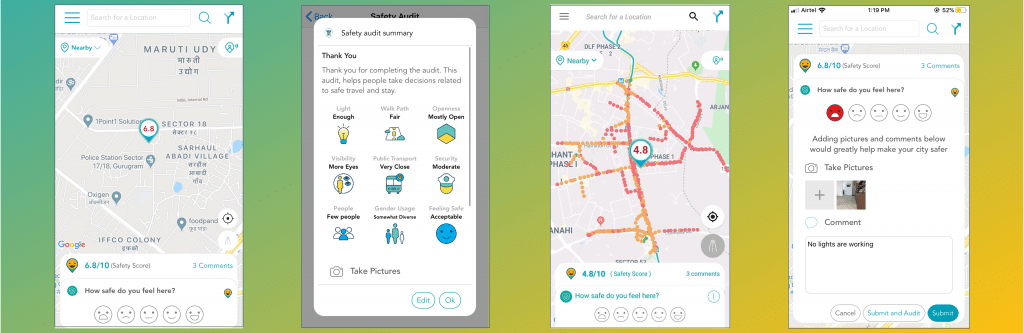

In 2013, Dr. Kalpana Viswanath and Ashish Basu started Safetipin, a social enterprise aimed at addressing the data gap around what makes places feel safe or unsafe, particularly for women, when navigating the city. There was a lot of general evidence to suggest that women felt unsafe in cities, but they wanted to really unpack that to see what exactly makes someone feel unsafe or feel safe.

»We focused a lot of the feeling, the perception, of safety because it is that perception that really drives the way we use a city,” Dr. Viswanath explains. “If I feel that Delhi is an unsafe city then I will not go out in the evening in Delhi, or if some part feels unsafe then I would not go there.«

As professionals working in urban safety, the team were familiar with use of safety audit tools to identify elements of the built and social environment that add to security or lack thereof. Safetipin translates those pen and paper tools into something digital, and through the application, provides a place for crowdsourced data from individuals around the world that can be seen by everybody as well. “Anyone around the world can do a safety audit about where they feel safe or unsafe,” states Dr. Viswanath. She goes on to explain that the goal is to try to obtain larger data sets, while also providing people from all genders a tool where they can make informed decisions about how they move around the city.

At the same time, the team has the vision and goal to share data with stakeholders. “The idea is not just to label a place as safe or unsafe, and once again put the burden back on women to not do this or not do that. Instead, we want to take this information to the people that can actually do something about it and work towards creating safer space and mobility options.” Dr. Viswanath emphasizes that they see technology as an enabler to creating social change – not an end in and of itself, but a way of reaching larger numbers of people and in some ways trying to democratize data collection as well.

Nearly 10 years on, Safetipin has worked in over 60 cities globally, with partnerships in 35 cities across 10 to 12 countries. Most of this work has been in India, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Among the many partners and funding sources, Dr. Viswanath notes that global development banks, non-governmental organizations, government agencies, educational institutions, and research institutions can bring a wide variety of knowledge and expertise that can be applied depending on the location and scope of a project. This also helps in the successful outcomes of a given project. For example, if a development bank is already working with a local government, the likelihood of that data actually being used by the local government increases.

“Additionally, when we work in a new city, we recognize we are not the experts of the city, we are not the ones who can make the process of change sustainable unless there is a local eco-system that is also engaged with it,” states Dr. Viswanath. She emphasizes it’s not just about funding relationships, but also collaborations with local, community-based organisations including women’s groups, universities and colleges, youth networks, etc. “It’s more representative and when we collect data and do advocacy work, we truly believe having local stakeholders involved is more meaningful.” Local ownership of data also has a better chance of being sustainable, scalable, and influential.

»We see technology and data as catalysts to support the work with a range of partners to advocate for change – which is only meaningful if it is done in partnerships.«

The relationship between Safetipin and its funders is also an important key to opening up greater opportunities. Dr. Viswanath notes a project in Bogotá, Colombia, which was won in part due to their partnership with CAF (Development Back of Latin America). “Partnerships are important to us because everyone brings something to the table, and they give a project a certain validity,” Dr. Viswanath explains. “We’re not just some organization, but rather part of a larger intervention and not just a one-off.” She goes on to emphasize that when looking at how to make cities safer, more caring, more inclusive, it is part of a larger process. Safetipin has their vision and goals–to provide access to data, empower users to make informed choices, and advocate for change in cities and partners are also looking to fulfill their responsibilities. While each partner is moving towards realizing their strategy, the alignment of their goals, missions, and strategies can help achieve a greater impact.

SHE RISES – A Framework for caring cities

Safetipin has done phneomenal work in raising awareness for the integration of care work in the understanding of daily mobility. Their recent publication breaks down the meaning of the mobility of care and gives valuable recommendations. Have a look!

Conclusion: Healthy resilience for gender equitable cities

It is critical for feminist development policies to move from being a nice-to-have to non-negotiable. If we are collectively committed to addressing the UN SDGs and to ensuring a just transition, then this needs to be a structural pillar of all foreign policy. Historically, feminist driven approaches such as gender mainstreaming have been incredibly helpful in starting the conversation about gender equity. However, the lack of meaningful integration into local and foreign policy means they have fallen short, often reduced in priority, or scrapped altogether when budgets are cut or with changes in the political landscape.

In order for these policies to be successful, it is imperative that they are drafted in collaboration with the communities that will benefit from it. External organisations cannot know every nuance of local dynamics, structures, and politics, but by working together, a balanced understanding can be reached to create more resilient programming and policies with lasting effects. This will be the true measure of impact, not just for climate resilience, but for what Jason Corburn refers to as healthy resiliencexv. Where climate resilience is focused on adapting and responding to stressors, healthy resilience looks at the current stressors and works to eliminate them for sustainable change, as shown in the following table:

Table 1: Healthy resilience vs. climate resilience

| Feature | Climate Resilience | Healthy Resilience |

| Principles | Adaptation to future shocks | Eliminate everyday vulnerabilities |

| Focus | Hazard mitigation | Enhance assets and community strengths |

| Orientation | “Bounce back better” | Dismantle structural inequities |

| Expertise | Technical outsiders | Lived experience |

| Change leaders | Government environmental agencies | Community groups and residents |

Source: Jason Corburn, Cities for Life; p. 183

The case studies, expert interviews, and research presented all point to the direct connection between successful programming and the combination of local groups with lived experience and knowledge, technical experts with global knowledge, and funding that can support these initiatives. The opportunities that feminist development policies present in creating access to that technical expertise is incredibly valuable to ensure states don’t have to be continually starting from scratch. Instead, global organisations can learn and adapt their approaches through working with local actors, strengthening the value of the knowledge, and providing examples for others to learn from.

But the inclusion of a feminist approach is imperative. The intersectionality of gender experiences, and the fact that those who identify as women represent a non-homogenous group of people comprising over half of the global population, emphasizes what stands to be gained when organisations commit to feminist thinking. Namely, everyone.

The future of cities everywhere, and the planet, depends on a shift to more sustainable transport. For that to be meaningful and resilient, it must include an examination of the existing status quo, and how current inequities impact the experience of women and other marginalized groups. A just transition cannot be possible without a gender equitable transition. The challenge is ensuring that this is not at the mercy of available funding or political will. To enact structural change at a global level, feminist economic development must become a structural part of any national and foreign policy. The question is not, is it necessary, but rather, what is lost if we do nothing.

Notes and References

i Throughout this essay I will refer to women as a group, with the understanding this includes anyone who identifies as a woman, including non-binary and transgender individuals.

ii Source: https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/Brief-Feminist-foreign-policies-en_0.pdf

iii Source: https://www.bmz.de/en/issues/feminist-development-policy

iv Source: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/transport-sector-co2-emissions-by-mode-in-thesustainable-development-scenario-2000-2030

v Wei-Shiuen Ng and Ashley Acker, Understanding Urban Travel Behaviour by Gender for Efficient and Equitable Transport Policies (International Transport Forum, February 2018)

vi Maja Bakran, Gender equality in transport: A precondition for innovation and sustainability (ITF “Transport Innovation for Sustainable Development: A Gender Perspective”, OECD Publishing, Paris.2021); p7

vii Source: https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/en/aussenpolitik/themen/feministische-aussenpolitik

viii Shannon Zimmerman, The value of a Feminist Foreign Policy (Women in International Security Policy Brief, February 2020); p2

ix Shannon Zimmerman, The value of a Feminist Foreign Policy (Women in International Security Policy Brief, February 2020); p3-4

x Jason Corburn, Cities for Life: How Communities Can Rebuild from Trauma and Rebuild for Health (2021); p168

xi Jennifer Thomson, The Growth of Feminist (?) Foreign Policy (February 2020); p3

xii Jason Corburn, Cities for Life: How Communities Can Rebuild from Trauma and Rebuild for Health (2021); p101

xiii Jason Corburn, Cities for Life: How Communities Can Rebuild from Trauma and Rebuild for Health (2021); p162

xiv Where Is My Transport, Decoding women’s transport experiences: A study of Nairobi, Lagos, and Gauteng (2022)

xv Jason Corburn, Cities for Life: How Communities Can Rebuild from Trauma and Rebuild for Health (2021); p182-183

Special thanks to the following interviewees for providing their time and insights:

Claudia Adriazola-Steil, Deputy, Global Urban Mobility Director for the World Resources Institute

Krishna Desai, Technical Expert at Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

José Segundo López Valderrama, International Data Coordinator WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities

Dr. Kalpana Viswanath, Co-Founder Safetipin