More likely to trip chain or to transport children and groceries, women around the world stand to benefit from easily accessible cargo bikes.

More likely to trip chain or to transport children and groceries, women around the world stand to benefit from easily accessible cargo bikes.

With vast gender differences impacting mobility choices, urban planners and researchers have been working to uncover workable solutions for closing the gap and ensuring women have the same transport opportunities as men. Some cities, like Tartu, Estonia, have approached this through a reconsideration of the built environment, reorganizing their city to create 15-minute areas, with facilities for everyday life — supermarkets, schools, doctors — all within a walking distance from the place of living.

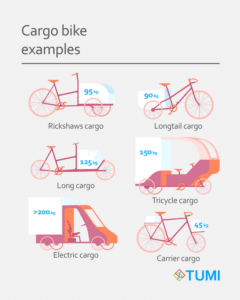

Yet we don’t all live in urban areas or have access to public transit; what works in some urban areas may not work for those living in rural communities. One solution to women’s mobility issues in both populous cities and more rural areas comes in the form of cargo bikes. Active mobility is a workable solution for nearly everyone, relying less on motorized means of transport and more on your own two feet; cargo bikes have, as a result, grown increasingly popular in cities across Europe. The bikes’ added capacity for carrying kids, pets, or groceries makes trip chaining by bike easier, especially with newer bikes outfitted with e-motor capabilities. As their use has spread, they’ve proven to be an effective means of closing the gender mobility gap for women.

Cargo bikes have likewise proven popular in several regions in Africa, proving a boon to women who would otherwise not have access to public transport or motorized means of mobility. Entrepreneur Wyson Lungu told TUMI in a recent podcast about his work bringing bicycles to women in rural Zambia to assist them in their everyday errands, from school runs to agricultural harvesting. Working with the cargo bike manufacturer Anywhere Berlin, they were able to create cargo bicycles capable of navigating the difficult rural terrain of Zambia’s interior. With these bikes, women are able to accomplish more in their communities, from hauling water to bringing crops to the market for sales. Lungu hopes to further outfit bikes with chilling technology that allow women to bring their agricultural goods to market without worry about spoilage.

The mobility gap in this region exists as a consequence of environmental challenges and the gendered division of labor; women are often forced to walk miles for basic necessities, such as hospital services. The introduction of inexpensive cargo bikes has relieved women of some of the burdens that have arisen as part of their care duties, freeing up their time and enhancing their earnings.

In Accra, Ghana, e-cargo bikes have likewise been put to use to better the economic situation of women. As scientists study the impact of these lower-emissions form of mobility, one expert look revealed that incorporating e-bikes capable of transporting heavy goods for use in delivery led to a 73% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions when these bikes replaced diesel-powered vehicles in the community. Another project, launched in March, aims to get electric cargo bikes into the hands of entrepreneurs, especially women or those from a socially disadvantaged background, who can use them as a less expensive means of transportation for their businesses.

As useful as cargo bikes have proven to be in these model cities, in the car-centric United States women with children remain reluctant to use cargo bikes for their travels, according to a 2018 study into attitudes and behaviors that might encourage switching forms of mobility. In the documentary, Motherload, which showcased the bikes’ growth in numerous cities across the country, one manufacturer noted that 75% of their customers were mothers. Still, safety concerns and limited infrastructure has hindered uptake in the US, leaving cities there well behind the rapid growth seen in European cities. As much as cargo bikes can make trips via pedals a viable alternative to cars, women’s safety concerns especially around cars drove hesitancy. That experience only reinforces the need for cities to rethink traffic planning to ensure bicycling and walking are encouraged. Women have shown themselves interested in alternative forms of mobility; now it’s up to officials to integrate them into the community.

References

Narayanan, Santhanakrishnan; Antoniou, Constantinos. (2022) Electric cargo cycles – A comprehensive review, Transport Policy, 116, 278-303, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0967070X21003644.

Riggs, William; Schwartz, Jana. (2018) The impact of cargo bikes on the travel patterns of women, Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 6:1, 95-110, DOI: 10.1080/21650020.2018.1553628

Schünemann, Jaron; Finke, Sebastian; Severengiz, Semih; Schelte, Nora, Gandhi, Smiti. (2022) Life Cycle Assessment on Electric Cargo Bikes for the Use-Case of Urban Freight Transportation in Ghana, Procedia CIRP, 105, 721-726, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2022.02.120.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information