How Jane Jacobs stood up against male-dominated, car-centered city planning

Author: TUMI

It’s almost impossible to imagine New York City without the hustle and bustle of its subway, the teeming diversity and uniqueness of its neighborhoods, and the sidewalks humming with life. Had it not been for the efforts of urbanist Jane Jacobs, NYC might have been a much colder, bureaucratic city, one that staunchly separated living from working from leisure.

Jacobs was a journalist who wrote stories about human-centered urban planning for Vogue, among other outlets. She resided in Greenwich Village in the 1950s at a pivotal time. New York’s “Master Planner” Robert Moses, architect of most of the state’s highways, was making plans for “urban renewal” and “slum clearance.” His plans involved extending Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park to improve the flow of traffic and provide access to the planned Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have passed directly through present-day SoHo, as well as part of Little Italy and Chinatown

Moses wanted to flatten working-class districts, unable to recognize the beauty in cultural diversity, in the familiarity of small villages within big, anonymous cities. His car-centric plans to destroy neighborhoods repulsed Jacobs and other locals, so she organized grassroots efforts to protect her neighborhood. In the process, she created the blueprint for the modern human-centered city, the counter-model to the trend at the time of the “ville radieuse”, the garden city.

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody,” she wrote in her 1961 treatise The Death and Life of Great American Cities. This book, touted by urban planners around the world to this day, strongly critiques Moses’s urban renewal projects which isolated poorer populations, particularly communities of color, to uniform apartment blocks and unnatural urban spaces on the outskirts of the city.

In a male-dominated industry, Jacobs faced opposition and derision at every turn, holding her head up high as mid-century men tried to belittle her by describing her as a “housewife” due to her lack of formal secondary education. Nevertheless, she persisted in organizing neighborhood meetings and demonstrations, collecting signatures, and mobilizing the former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to join the cause. Her efforts proved successful, and on June 25, 1958, the city closed Washington Square Park to traffic, thus preventing Moses’s building project.

When women are involved in urban planning, they plan for all

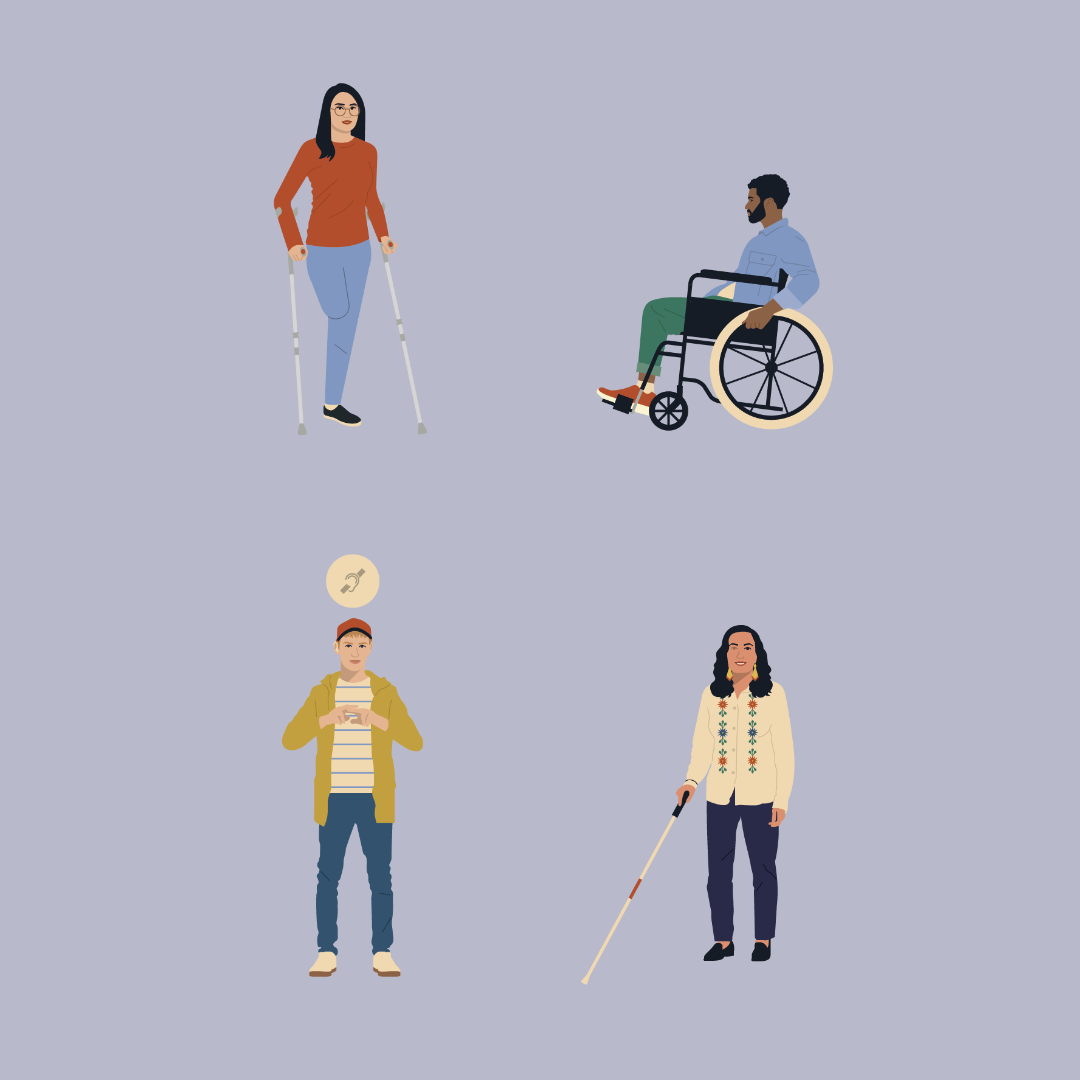

The fight between Jacobs and Moses is a quintessential example of the way men and women look at cities and urban planning. Even though Jacobs was instrumental in formulating ideas about vibrant, dense, mixed-use neighborhoods making up a city, most cities in general, and public transit in particular, are still built by men, for men. Just try being a parent with a stroller running errands on New York City’s subway system, or a woman attempting to avoid harassment on the train at night in a low-income neighborhood, and it’ll become glaringly obvious just how little input women have been able to contribute to transport planning. Therefore the needs of half the population, not to mention the able-bodied, have been considered in transport planning only slightly.

Jacobs has attributed this difference in mindset to the idea that women think about things close to home, such as what’s on their street, in their neighborhood, and within their community. Women can see the big differences that small things can make in a city, the patchwork of social infrastructure like mass transit and libraries, or large urban networks made of smaller parts like neighborhoods. Men, she said, think big, national, global. They are bureaucratic and top-down. Women’s brains reward them more for pro-social and generous behavior, and men’s brains reward them more for selfish behavior. So really, who should be in charge of city planning?

Today, we celebrate a range of other women who have stood up to the male-dominated and car-centric model of city planning, as well as the growing recognition that gender-inclusive mobility is sustainable mobility.