It’s time for women to be front and center in the movement for cities.

It’s time for women to be front and center in the movement for cities.

The original article was published by nextcity. Find it here: Urban Planning Has a Sexism Problem – Next City

Take a moment to look around you. Really look. See the city — the streets, the buildings, the spaces between them — and realize for a moment that virtually everything you see has been designed and shaped by men.

Now imagine what it would be like if it were women-led.

Since at least the agricultural revolution roughly 12,000 years ago, women have been in a near-constant state of subjugation — physically, socially, or politically — by the opposite sex. We are finally at a point in history where certain women are at the greatest level of privilege experienced since humanity settled in cities. And there’s no debate that we have seen incredible gains for female representation over the last hundred years in fields like architecture and city government.

But this progress has been incremental, limited to a select privileged (lighter-skinned) few, and women remain seemingly consigned to supporting roles in an urbanism movement many argue was in fact founded by a woman — Jane Jacobs. Today’s urbanism emphasizes many core beliefs that Jacobs espoused: “eyes on the street”, the messy joy of urban complexity, and the need for social interaction through human-scale urban design. Her ideas are taught in urban studies and planning courses around the world. Yet if my experience is any indication, Jacobs — and only a handful of other select women — are the exceptions, in a field otherwise dominated by men.

My wake-up call came when I realized one very striking fact: nearly all of my references for urban best practices, as taught to me in higher education, were written by men.

You can go through any urbanist’s bookshelf or City Reader in your average syllabus and find an abundance of (mostly white) male authors. Even accounting for the obvious gaps from periods when women were officially unwelcome from the architecture and urban planning fields, the Y-chromosome bias is overwhelming. Check out this table of contents from a 2016 edition of the Routledge City Reader in the British publisher’s Urban Reader Series. The volume includes articles by 66 named contributors. Four are women: a startling 6 percent. Urban Planning Today, A Harvard Design Magazine Reader, published in 2006 by University of Minnesota Press includes 13 contributors. Two are women. UMN and Harvard did better than Routledge with 15 percent — but that’s hardly progress.

And then there is the maleness of the pop urbanism circuit. After all, once you move outside of academia’s libraries and lecture halls, there is a growing (and profitable) industry built around buzzwords coined, it seems, mostly by men. To name a few: Richard Florida (Creative Class), Jeff Speck (Walkability), Fred Kent (Placemaking), Jan Gehl (Cities for People), Gil Penalosa (8 80 Cities), Andres Duany (capital-”N” New Urbanism), Mike Lydon and Tony Garcia (Tactical Urbanism). Inside urbanism’s insular world of email lists and conference circuits, these men have created a new language spoken by few, with an influence felt by many.

Of the more than 100 seminal texts and buzzwords compiled from my higher education experience and professional career as an urban anthropologist, fewer than 20 percent are by women and virtually none are by women of color.

Now, that’s my list. There are others, to be sure, but they all seem to follow the same general trend. Planetizen’s top 20 urban planning books of all time includes only two books by women: The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs (at number one, naturally) and Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. Both of them are white, of course. That’s to say nothing of their 2017 “most influential urbanists of all time” crowd-sourced list with only 17 percent female representation, technically an increase from 9 percent when the list was last compiled in 2009. Of the 15 women of the list, three are women of color (one of the precious few is Rosa Parks).

Had any of this not been counted before? If Jane Jacobs always tops the list of urbanists, then — pardon the expression — where my ladies at? Suzanne H. Crowhurst Lennard, for instance, was in the room with the pioneers of urbanism, as was Margaret Mead, the famous cultural anthropologist and compatriot of Jane Jacobs. Where are they on the list? Mindy Fullilove literally wrote the book on the mental health impacts of urban renewal, displacement and segregation yet her work is missing from many contemporary planning anthologies. Tamika Butler drives the diversity and cycling conversation with refreshing honesty and experience. Likewise, Lauren Elkin’s recent book Flâneuse added a previously nonexistent feminine version of the masculine word for “urban wanderer” to our lexicon.

We also cannot discount the thousands of influential women who are running cities as mayors and other public officials, teaching about cities as urban planning and architecture professors, leading urbanist organizations and working in communities to change the way we design — and live in — our cities. But as the so-called second sex knows all too well, doing the work and getting recognized for it are two very different things.

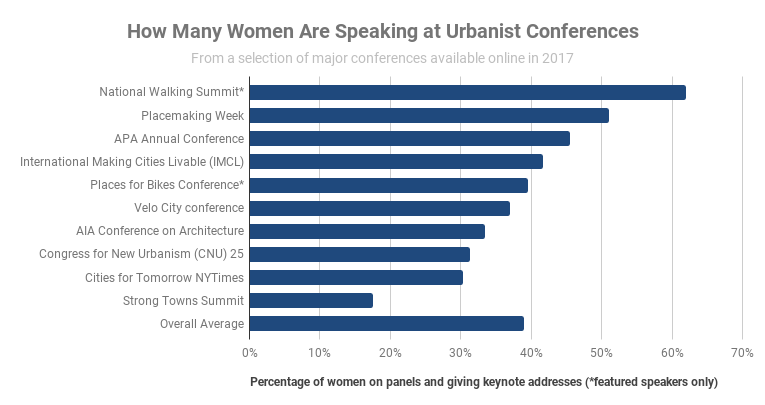

If you’ve ever been to an urban planning or design conference, you are likely very familiar with the all-male panel (check out #manel for some catharsis or better yet — sign on to commit to not participate in all-male panels here). You may also have noticed an overwhelming tendency toward male keynoters. When I tried to put numbers behind the anecdotal inference, I discovered that no major urban organizations keep public data on gender representation at these events. A quick hand-tally of identified participants on panels and keynotes at 10 major urbanism conferences during 2017 revealed roughly six out of every 10 public speakers on the urbanist circuit are men.

It’s as if our education, popular discussion, and the entire urban world around us is a foreign environment for half of the population that moves through it. As Valentine Njoroge, a feminist writer from Kenya puts it, “It’s like we walked into a man’s bathroom.” Creepy.

One of the most recognizable women in contemporary urbanism is Janette Sadik-Khan, former Commissioner of the NYC Department of Transportation and author of “Streetfight: Handbook for an Urban Revolution.” Perhaps more than many of us, the Bloomberg Associates consultant is optimistic. “The increasing number of women now planning and designing cities are rewriting the rulebook and breaking the car-obsessed traffic dogma that’s kept streets unchanged for half a century, ” the former commissioner told me in an email.

So, women urbanists exist and some of them — again, particularly white women — are finding themselves in positions of power. That much was never in real doubt. Why then do we still see bookshelves full of male authors, urbanist conferences with all-male panels, or the proliferation of male-led urban buzzwords and businesses? There’s clearly still a lack of representation at the top, so what are we missing by having fewer women involved? What explains this allergy to women-led urbanism, and further, an outright resistance to urbanism led by women of color?

The answer may be more straightforward than we may want to think. “If you have the same people around the table who have been trying to solve the same challenges for 50 years, nothing will change,” says Lynn Ross, former vice president of Community and National Initiatives (CNI) program at the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. “I think it’s important to have women not only at the table, but women running the meeting, setting the table, bringing voices in and leading. She has a variety of perspectives, as a caretaker, as a mother, as a sister, but also — she’s an urbanist — and she has something to say about cities and how they work.”

Allison Arieff, editorial director of SPUR and New York Times columnist (and Next City board member), sees the problem of underrepresentation perpetuated, even as overall engagement in urban issues grows: “What is […] frustrating is the entrenched old guard wedded to old paradigms, uninterested in testing or exploring new ones. What is probably even more terrifying than that is the number of engineer-driven tech companies that see cities as algorithms able to be programmed and controlled. Cities are NOT that. They are messy, visceral, unpredictable — and wonderful.” Years after Jacobs’ infamous battle against the top-down planning of Robert Moses, are we still facing the same problems?

One thing is clear: When we increase diversity in the conversation, we improve our fundamentally heterogeneous, intersectional, and always evolving urban environments. If we are to tackle our urban future with the full abilities that humanity has to offer, we’re going to have to add women of all ethnicities and experiences to that list.

We are half the species, after all.

If women’s rights are human rights, it stands to reason that a feminist city is a humanist city. While it’s true that a woman’s body may not be a feminist mind and not every female urbanist shares the same values, it is still the case that women bring with them a set of experiences that differ in meaningful ways from those of many of their male peers. (No less relevant is the fact that women of color bring a whole other set of experiences, distinct from white women.) Whether overt or not, these various urban interactions inform the way we read cities and the approach we take to addressing their challenges. It’s easy to say that we’re planning with equity in mind yet we continually end up short. A woman-led city offers the possibility of bringing together all gender identities, all abilities, ages, and ethnic backgrounds, around the unifying concept of respecting women and girls.

And some cities agree. More than general equity, an emphasis on age, or a branded idea, women from Liberia to Austria are applying feminist leadership to their urban form from the policy level down. In Vienna, they use “gender mainstreaming,” based on a United Nations initiative, to create a feminist city. At Habitat III, the female mayors of Barcelona and Paris, Ada Colau and Anne Hidalgo, pushed for the Right to the City concept to be included in the New Urban Agenda to ensure that every citizen’s needs are met in a city. And that’s to say nothing about the overarching gender equality initiatives in some Scandinavian countries, including a feminist planning initiative by and for women in the Stockholm suburb of Husby.

In the United States, there are signs of progress as well. Walk into any architecture or urban planning classroom in the U.S. and nearly half of new students are women. This number only rises when you also consider social sciences like public health, community development, and urban anthropology or environmental psychology. In the latest report put out by the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB), 42 percent of graduates in architecture were women (not too shabby for a field that banned women from becoming licensed architects until 1972 in some cases), while 52 percent of urban planning graduate students in 2016 were women. We’re even finally making a dent in city hall, with roughly 25 percent of the top 100 cities in the United States now boasting female mayors.

Women in cities around the world are finally coming together to share their experiences, to strengthen the case for making this the central issue that can take our cities to the next level of not only livability, but lovability. There is a gap in representation, a gap in recognition, and a gap in leadership — all of which can impact the way we live our urban lives.

This is about more than street harassment or assault.

This is about more than women-only train cars.

This is about more than better street lighting.

This is about more than closing the gender gap in urbanism.

Ada Colau, the first female Mayor of Barcelona, has it right when she says, “right now we have an opportunity for those individuals who have traditionally been let down as ‘second-class citizens’ to become the main characters.” To me, this is about starting a movement around truly women-led cities from all aspects of urbanism: from policy to community development, street artists to architects, all aspects of urban planning/design/research and beyond. For every woman, regardless of privilege. This is about achieving what we have never had the opportunity to impact before: the design and management of our cities, by and for our fellow women.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information