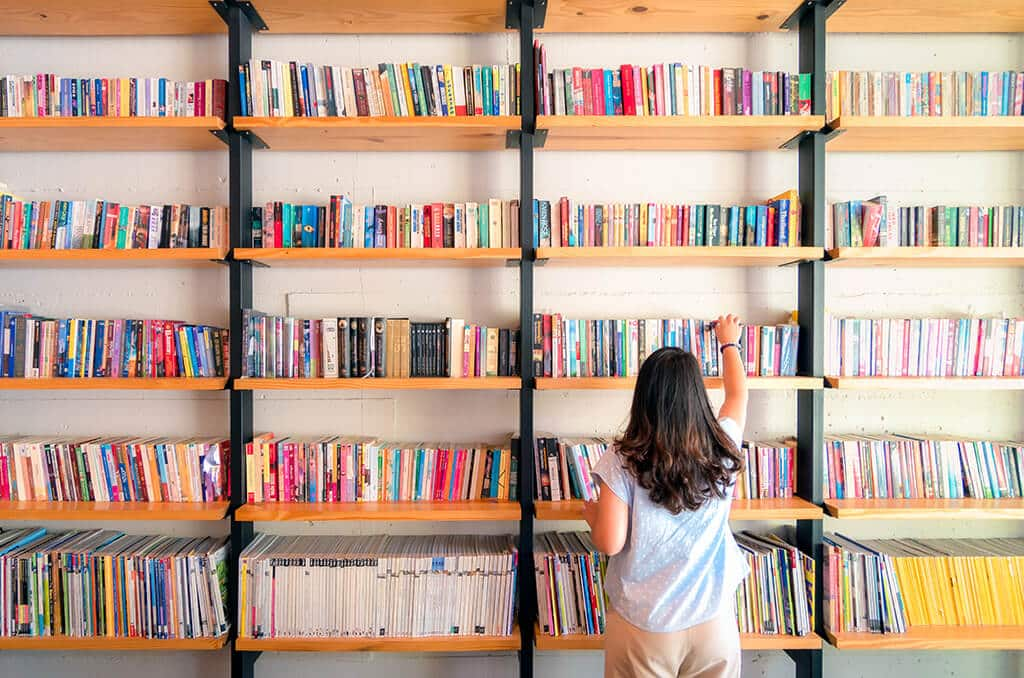

Personal safety on streets and public transport is one of the main barriers women and girls face in accessing important services such as health care, education and other economic opportunities. This blog is shaped by my personal experience as a young Mexican woman who relies on walking, cycling and public transport. It looks at the importance of women’s advocacy and participation towards more inclusive and sustainable transportation systems that ensure their right to the city in Latin America.

By Sonia Medina

, we have all felt unsafe while walking back home, decided at least once not to go out alone at night, to spend more on “” modes such as Uber or have taken longer routes to avoid quiet areas. In the last years in many Latin American cities the reported violence against women and girls in streets and public transport have dramatically increased. The news is inundated with reports d not arrive home. These endless reports lead us to have a greater fear of going out freely and wearing what we want, since no mode of transportation is truly safe enough. This fear has been created not only by the knowledge that something has happened to someone we know, also because we ourselves have been harassed, catcalled, or even raped.

The impact of sexual harassment on women’s daily commutes in Latin America

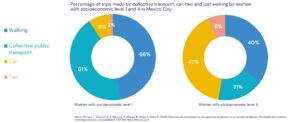

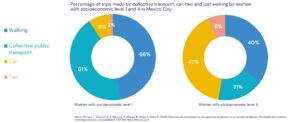

Fear for our safety while commuting affects all women differently. Teenage girls’ traveling in Mexico City often must endure and resist sexual harassment in order to be able to go to school or attend other activities. Many of us use informal public transportation, where the bus stops are not well defined, the time schedules are unpredictable, and the stops are isolated, dirty, and dark. On the other hand, teenage girls from wealthier families can’t wait to reach the age of 16 to obtain a driver’s permit, so that they can drive themselves around free from harassment. Similarly, adult women with higher incomes use private cars in order to feel safer while women with lower incomes rely on walking and public transportation. Women who don’t have access to a private vehicle need to introduce coping mechanisms like taking other routes, or not walking alone; even if these alternatives are not the fastest, the most convenient, or economic*1*2. Others consider the bicycle as the best way to move independently, economically and even more safely despite the lack of safe infrastructure. As primary care givers women transfer their safety concerns to their children, which could influence the childrens’ mode choices in their adult lives*3.

The lack of safer streets, cycling environments and public transport systems result in women being socially excluded and increases poverty as it limits access to basic services, education, work and participation in leisure and cultural activities. A study conducted in several Latin American cities reveal that a “number of participants who had stopped studying, working [did it] because of a particular incident or the level of threat they felt”*4. I, in Lima, (2%) stopped attending school, work or college because of their experience of abuse and harassment. In short, the current transport systems limit our fundamental the city.

Actions can be taken to empower women and improve their traveling experiences

Improving women’s travel experiences is key for cities to move towards more inclusive sustainable modes of transportation. To achieve this, complete and safe streets, cycling infrastructure and public transport are crucial to ensure a just transition in transport that provides equitable access to opportunities through sustainable modes of transportation. Integral strategies considering infrastructure and operation measures, outreach and education, and regulation and law enforcement should be followed to build gender-responsive transportation systems that can enable women to choose sustainable modes. Some Latin American cities are implementing different actions:

Women are mobilizing and taking action to address sexual harassment in urban transport and to ensure that their experience of daily commutes won’t be overlooked. For instance, Observatorio contra el Acoso Callejero in Chile, Mumala in Argentina and AmorrAs Taxis in Mexico City are civil society organizations campaigning against sexual harassment, collecting data through surveys to shine a spotlight on the challenges women face while travelling in public transport and providing women only taxi services to respond to the lack of a safe transportation systems.

To achieve substantial change for safer and inclusive transportation systems, girls and women’s participation in decision making is crucial. Women are key agents of change. Their voice and their participation in improving transport options is essential to reveal and address the problems that affect them*5.

Prioritizing safety in transport planning will allow women who walk, cycle, and use public transport to make their journeys enjoyable, and them to choose any transport mode without fear and independent of their income level. Likewise, it allows women to participate in daily life, work opportunities and social activities. As long as fear and danger keep limiting women’s travel behaviors, much-needed transformation to equitable and sustainable transport systems will not be achieved.

- Mejia, L. (2018): An example of working women in Mexico City: How can their vision reshape transport policy? Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, (116), pp. 97–111. p.17 DOI

- Dominguez, Karla, A. Machado, B. Alves, V. Raffo, S. Guerrero and I. Portabales. (2020). Why does she move? A study of women’s mobility in LAC cities. Washington. D.C.: World Bank Group.

- Allen, H. (2018) ELLA se mueve segura: Un estudio sobre la seguridad personal de las mujeres y el transporte público en tres ciudades de América Latina. Caracas: CAF y FIA Foundation. P.83

- Plan Internacional (2018): Unsafe in the city. A research report on girls safety across five cities. p.19 23.08.2022

- LIFE Bildung Umwelt Chancengleichheit (2022): Equal Mobility. Gender Just Mobility in Practice. p. 39. 25.08.2022