The rapid growth of electric cycles and micro-mobility options is not a new phenomenon. For the past decade (or more) an increasing number of more sustainable, electric-powered vehicles have showed up on streets around the globe. Some are successful, some less-so, but their prevalence has not dissipated over time. I recall a trip to Los Angeles in early 2018 and witnessing the impact of the explosion of Bird scooters throughout the city, and it hasn’t slowed down since. My initial thoughts were, “It looks fun! And hey, they’re not in a car, so that has to be a good thing, right?”

The image of electric mobility, however, has had a rather binary evolution. Aside from the electric kick scooters, many people’s impressions of vehicles within this field are that of someone looking for speed, often male, to use for intense, long-distance commutes, like on a fast electric bike. The reality is that the landscape of electric micro-mobility is vast and ever-expanding. With the suite of options available, it is also having an impact on the inclusivity of mobility on streets around the world. The recent release of Women Mobilize Women’s Remarkable Women in Transport 2022 highlights the countless women working in the field of electrification, many focused on how electric mobility is increasing access to transport. So just how are electric cycles and micro-mobility enabling more inclusive transport?

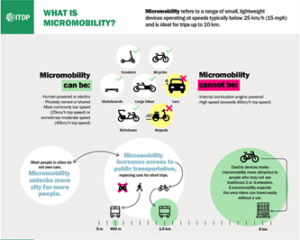

What is micro-mobility?

A good place to start is first demystifying micro-mobility. I think for a lot of people, the term brings to mind kick e-scooters, “hoverboards”, and many of the new smaller human transport tools that have arisen in recent years. In reality, micro-mobility devices are typically smaller, lightweight and operate at speeds generally lower that 25 km/h (15mph). Basically, everything from a skateboard to a cargobike can fall into this category. As long as it doesn’t have a combustion engine and/or doesn’t go faster than 45km/h, it’s micro-mobility. ITDP has created a great infographic to explain this.

Micro-mobility and gender equitable transport

Now that we know what micro-mobility can be, how is it impacting transport equity? From a gender perspective, electrification of cycles and cargo bikes help women continue performing their care trips regardless of distance or family size. Although things are moving towards a greater balance, the global gender care gap is still significant, with women continuing to take on the majority of household and other unpaid care duties. With an electric cycle or cargo bike, taking the kids to childcare and/or school and then hopping around town to run errands, buy groceries, or other trips becomes a bit easier with pedal assist. Combined with a fine-grained network of traffic-calmed streets and cycle tracks, this kind of trip-chaining is simplified, making cycling a more viable and efficient option.

This is reinforced with the fact that, in the Netherlands, a country with vast cycling networks, women made 85% more e-bike trips than men, travelling 14% further distances (2.2 billion km) (KiM, 2019). In hillier typographies, or places with warmer climates, e-cycles also help remove sweat and strain from the equation, eliminating many of the barriers that often influence women’s choices to go by car instead, or the time-cost of having to negotiate potentially disconnected and infrequent public transport.

Figure 1: Electric Cargo Bike (Credit: Bruntlett)

What is often less discussed and with little research available on the topic is the social safety that can be provided through shared micro-mobility, be it a bicycle, e-scooter, electric moped, or otherwise. For women using public transport, it can provide a fast, effective, and safe door-to-door option for travelling alone. Many women are very familiar with walking alone at night with keys in their fists because their transport choice doesn’t not bring them exactly where they need to go. Dockless e-bikes and e-scooter share have the potential to shorten the length of that trip, helping to potentially reduce some of the fear and anxiety, and delivering them right to their front door. Of course, these tools alone won’t improve feelings of safety in poorly lit areas or quiet backstreets, but they can be part of a larger solution to creating safer transport options for women.

Age equity

When discussing electric micro-mobility, as with most transport conversations, the focus tends to be on adults between the ages of 18 and 65. Crucially, this is also the age at which most people can legally operate a motor vehicle. This, however, overlooks the fact that everyone has a point in their lives when they are not able to do so, namely during childhood and our senior years. Electric cycles and micro-mobility devices can and do present very accessible and inclusive mobility choices for both the young and old.

Inclusive transport means that regardless of one’s age, ability, or background has access to options. This includes geographic location. Although populations in large cities are growing, many families still choose to live more rurally. Just as an e-bike has the potential to increase the travel range for someone commuting to work, the same is true for school-aged children who have to travel long distances to access educational institutions. Reduced or non-existent budgets in many locales mean that not every child has the option to take a school bus or public transport to school, or have their parents drive them to school. It’s no surprise then that many Dutch teens living further afield travel to school by e-bike. Not only does it mean they can maintain vital access to education, but also the independence to travel to extra-curricular activities, part-time jobs, and social gatherings, without having to depend on their parents.

Figure 2: Electric Tricycle (Credit: Bruntlett)

On the other end of the spectrum, electric micro-mobility is enabling autonomy and freedom of transport for seniors. The average adult is outliving their ability to safely operate a motor vehicle by 7 to 10 years. At the same time, their endurance and stamina also begin to diminish. Access to electric cycles make it possible for people well-into old age to cycle longer without too much strain, and without dependence on family, friends, or public transport. Other micro-mobility tools like mobility scooters extend that independent mobility even further as then begin to struggle with balance, ensuring that even our oldest community members can remain an active part of the social fabric of our towns and cities.

Inclusive mobility for all abilities

Universal Access Design aims to ensure that no one is limited in their access of the public realm because of their individual abilities. However, there remains a misconception in many places that people living with a disability need a car to access the city, when in fact the opposite is true more often than not. In the United Kingdom, for example, 60% of people living with a disability don’t have access to a car, either through personal ownership or the support of a friend of family (Aldred, 2008).

Figure 3: Maya Levi on her scootmobiel in Delft (Credit: Bruntlett)

Electric micro-mobility options positively impact the inclusive access for those individuals. Like with seniors, electric mobility scooters are an essential transportation tool for maintaining independence. In an interview with my friend, Maya Levi, who lives with multiple sclerosis, she refers to her mobility scooter as a tool of empowerment, allowing her to access her city, pick up her kids from school, and do nearly everything she was able to do before her diagnosis. Similarly, the range of cycles available, like tricycles and quadricycles, when electrically powered, allow individuals with a variety of physical limitations to comfortably move around their communities. Micro-mobility cannot solve every challenge, but it certainly is helping to create a more inclusive mobility landscape.

Furthermore, programmes like the Rickshaw project from Karachi, Pakistan, although not an electric solution at this time, demonstrate how people with walking disabilities can operate smaller forms of mobility. Individuals can operate rickshaws both as passengers and as drivers themselves, providing not just a micro-mobility tool, but also a form of autonomy. The Autorickshaw, developed by the Rickshaw Project operates with hand controls for an operator with a disability, as well as space for transporting passengers with disabilities. Because of the scalability of these small vehicles, fuel-powered rickshaws have the potential to also be offered as electric vehicles in the future with investment and further innovation.

Variety of transport options for resiliency

Throughout the pandemic, and with the increased frequency extreme weather events, it has become clear how fragile car-based networks can be. Looking ahead, they need to be more resilient to survive challenges to come. The availability of electric micro-mobility options ensures that in cases like fuel shortages, weather disruptions, changes in public transport availability, people can maintain their access work, school, and essential services. When these offerings are combined with a comprehensive, intuitive, and safe mobility network including separated cycle–or mobility–lanes, accessible storage and charging stations, and public transport networks, e-micro-mobility can be part of a more resilient future.

Challenges such as cost and availability remains barriers to entry for many, however with greater investment in shared-mobility systems, as well as government subsidies for electric cycles and micro-mobility devices – such as those in Italy and Portugal – help soften the initial cost for individuals. Put into perspective, for those individuals living on limited incomes, the cost to invest in in an electric cycle or micro-mobility device is dramatically lower than the cost to own and operate a car, providing a more accessible option for those with reduced means. Electric micro-mobility helps to level the playing field for more people than we may think, and for any future to include more equitable transport, it needs to be a key part of the conversation.