In June 2023, Karnataka introduced the Shakti program, providing free bus passes for women and transgender residents, marking a bold step towards just mobility and inclusion. This initiative has significantly eased financial burdens, empowered women by enhancing access to economic and educational opportunities, and fostered greater freedom of movement. However, challenges like overcrowding, safety concerns, and revenue loss must be addressed to ensure the program’s long-term success and impact on public transportation.

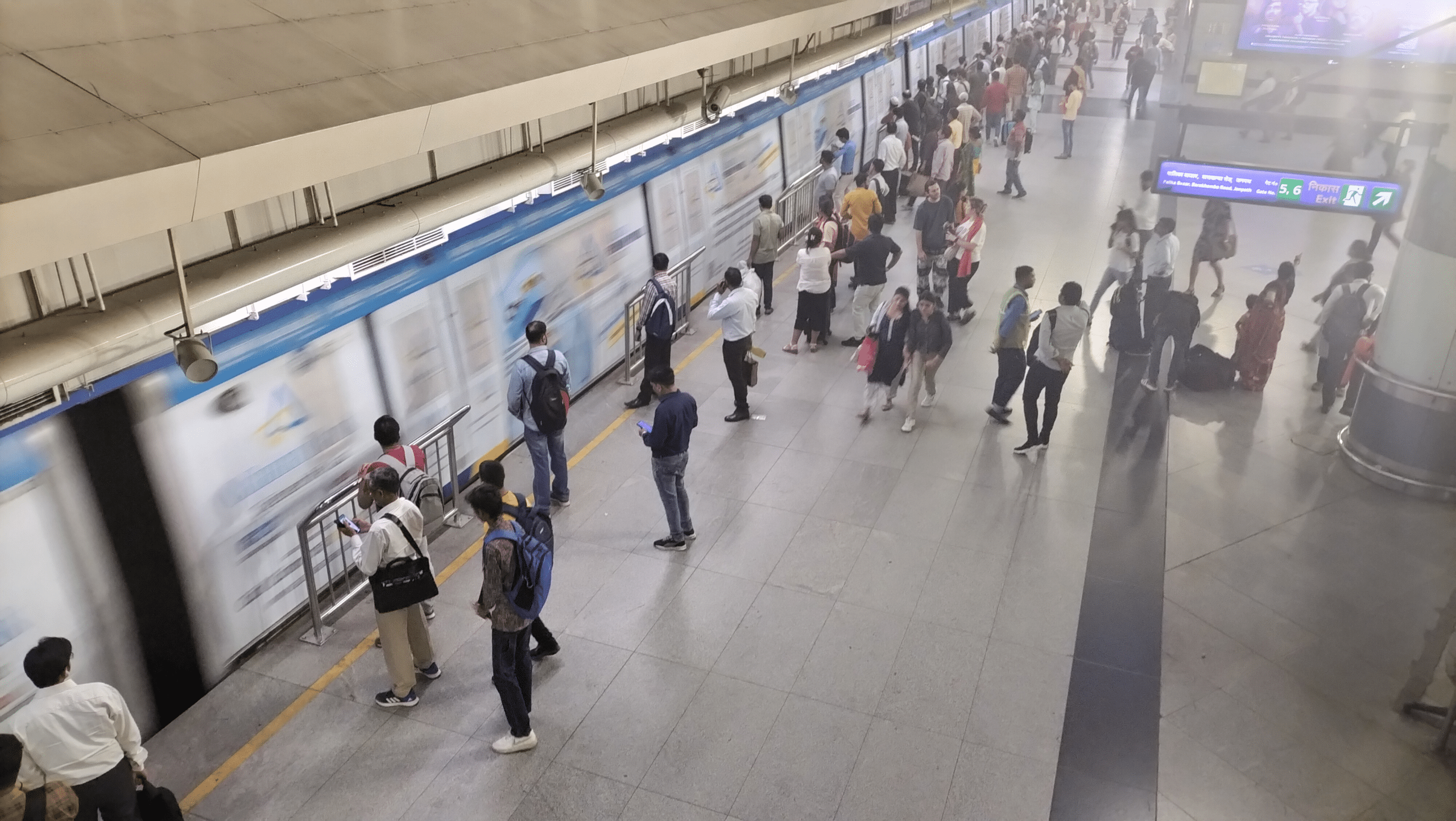

A wave of vibrant images flooded the pages of major newspapers across India in June 2023. Photos of packed buses brimming with smiling passengers were not just ordinary scenes They hailed from Karnataka, a Southern Indian state, that has recently unveiled a revolutionary program: free bus passes for women and people of the transgender community.

This bold move by Karnataka underscores a growing recognition of the importance of just mobility and inclusion in public policy. By providing free transportation, the state is not only easing the financial burden on women and transgender individuals but also fostering greater freedom and equality. This article will delve deeper into the program’s impact on empowering women and transgender public transport users and move a city towards more sustainable, inclusive, and just mobility.

Free bus passes: unlocking economic opportunities for women

Women are the biggest users of public transport in India. According to the World Bank, they use public transport for 84% of their trips. However, these trips often involve safety and accessibility concerns, with high cases of sexual harassment (according to one study, 25 percent of young women reported being sexually harassed on public transport), and low connectivity to peripheral urban and more rural areas.

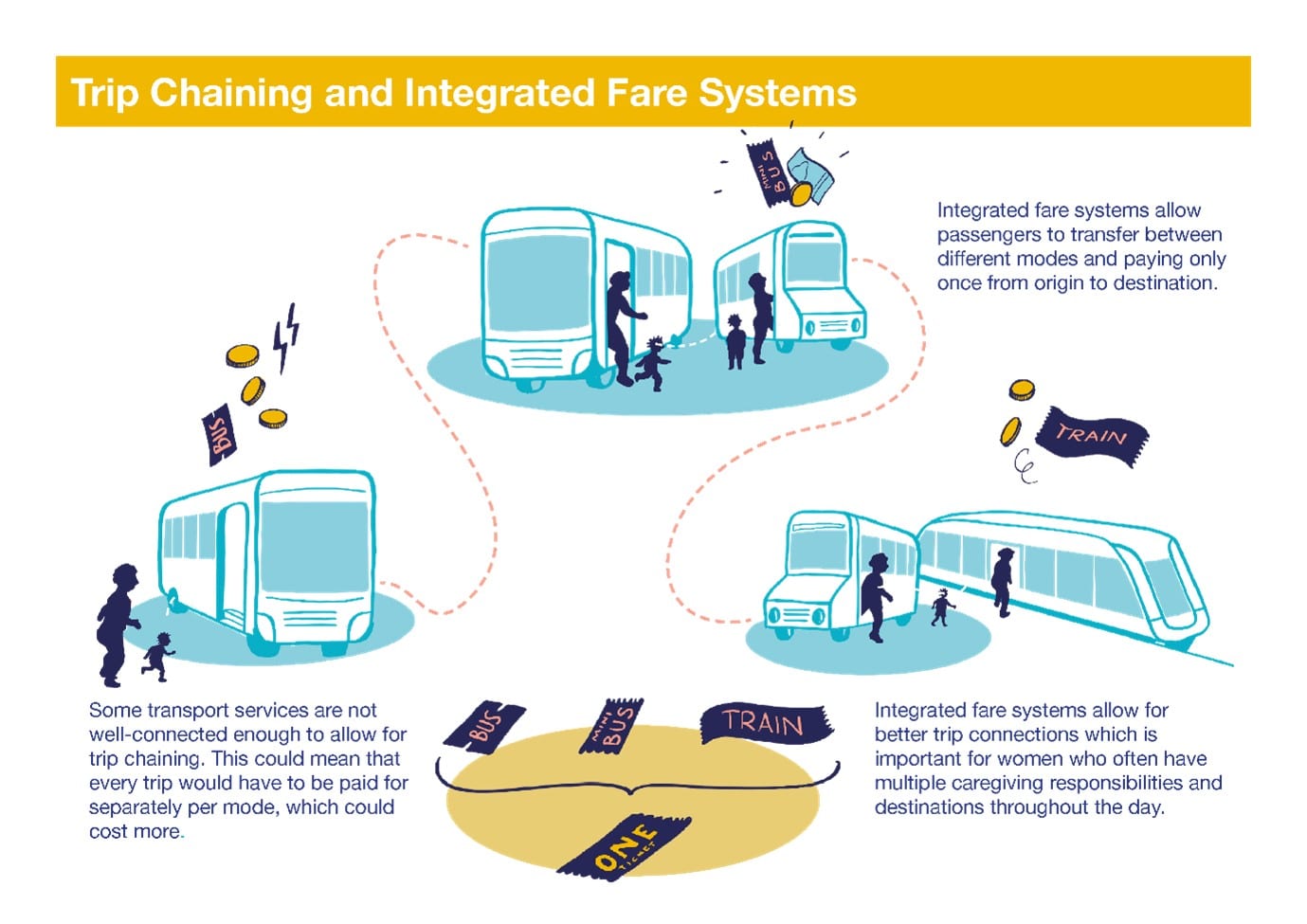

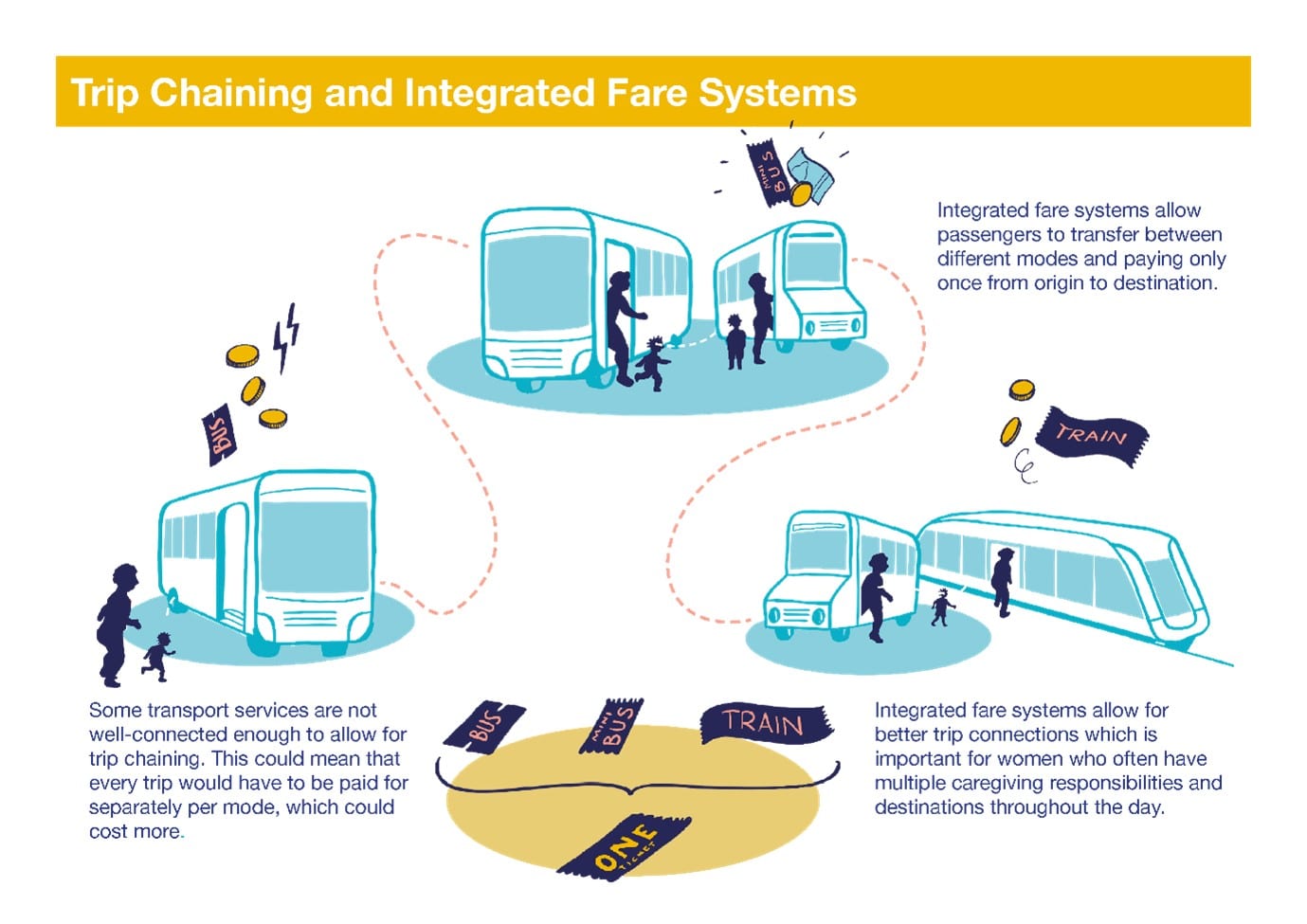

It is essential that women feel comfortable on public transport since this mode of transportation is key to their increased participation in the labor force. As it stands, labor participation of women in India is one of the lowest in the world, with an employment rate of less than 30% for women over the age of fifteen, according to the World Bank. Often, men restrict the financial options available to women and object to them working outside the home. By law, women are free to work, but expensive or unpredictable commute can deter them. Instead, they often walk to their place of work or to local conveniences, restricting their employment options to a limited radius of a few kilometers around their home. Trip chaining, i.e. grouping several errands into one trip rather than returning home in between, can also be challenging and expensive in this context since every trip is charged.

The Shakti program, meaning “strength” in Hindi, is being trialed in all cities with the state-run bus services of Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation (KSRTC). This initiative offers free bus passes to all female and transgender residents, aiming to boost access to economic and educational opportunities that may have otherwise been too inaccessible for them to travel to. By easing transportation costs, the Shakti program not only promotes financial freedom and promotes workforce participation, but it also saves time otherwise spent walking to places like shops or care facilities.

Proven Success of Free Bus Schemes: Lessons from Delhi, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka

Similar initiatives from other Indian cities have proven successful. In 2019, the Delhi Government introduced the ‘pink slip program’, providing free bus rides to all women in the city. Women receive a pink ticket from the conductor upon entering the bus terminal, which the government reimburses to the bus operator with Rs 10 (0.11 euro). Within 20 days after the launch of the scheme, daily female ridership increased from 33% to 44%. This program was renewed in early 2024. Evidence from the capital city shows strong support for such schemes, with over 40 million women riding buses for free within the first nine days of the program.

The states of Punjab and Tamil Nadu followed suit and established a free bus ride scheme for women in 2021, allowing free travel using public buses. From July 2021 to March 2022, the percentage of women commuting by bus in Tamil Nadu increased from 40% to 61%. This led the Government to increase the budget of the program from $168 million in its first year to $212.8 million the following year.

Karnataka’s pilot cities have also reported success. According to the state’s department of transportation, 6.2 million women have used the scheme within six months of its launch. This program not only improves access to economic opportunities but also empowers low-income women to save money, manage their time better, and visit tourist destinations they might not have considered before. Users have reported that they appreciate the freedom to travel without restrictions, as free public transport eliminates barriers that might otherwise limit their movement. For the participating cities, the scheme has been easy to implement. Women simply show their resident ID with no need for special tickets or smart cards.

Challenges and Criticisms of the Shakti Program: Accessibility, Overcrowding, and Safety Concerns

Despite the positive response and the simplicity of the scheme, Shakti has encountered some criticism. While the program aims to support lower-income women, many affluent women are also benefiting from the scheme, impacting bus provider revenues. The scheme is accessible only to women with Indian nationality, excluding migrants. Some more conservative political voices have expressed concerns about “unfair freebies”. Rude behaviors of the front-line staff towards women have also been observed. Private transport providers, including bus operators, auto-rickshaw drivers, and taxi drivers, opposed the scheme and went on strike in Karnataka a month after its launch.

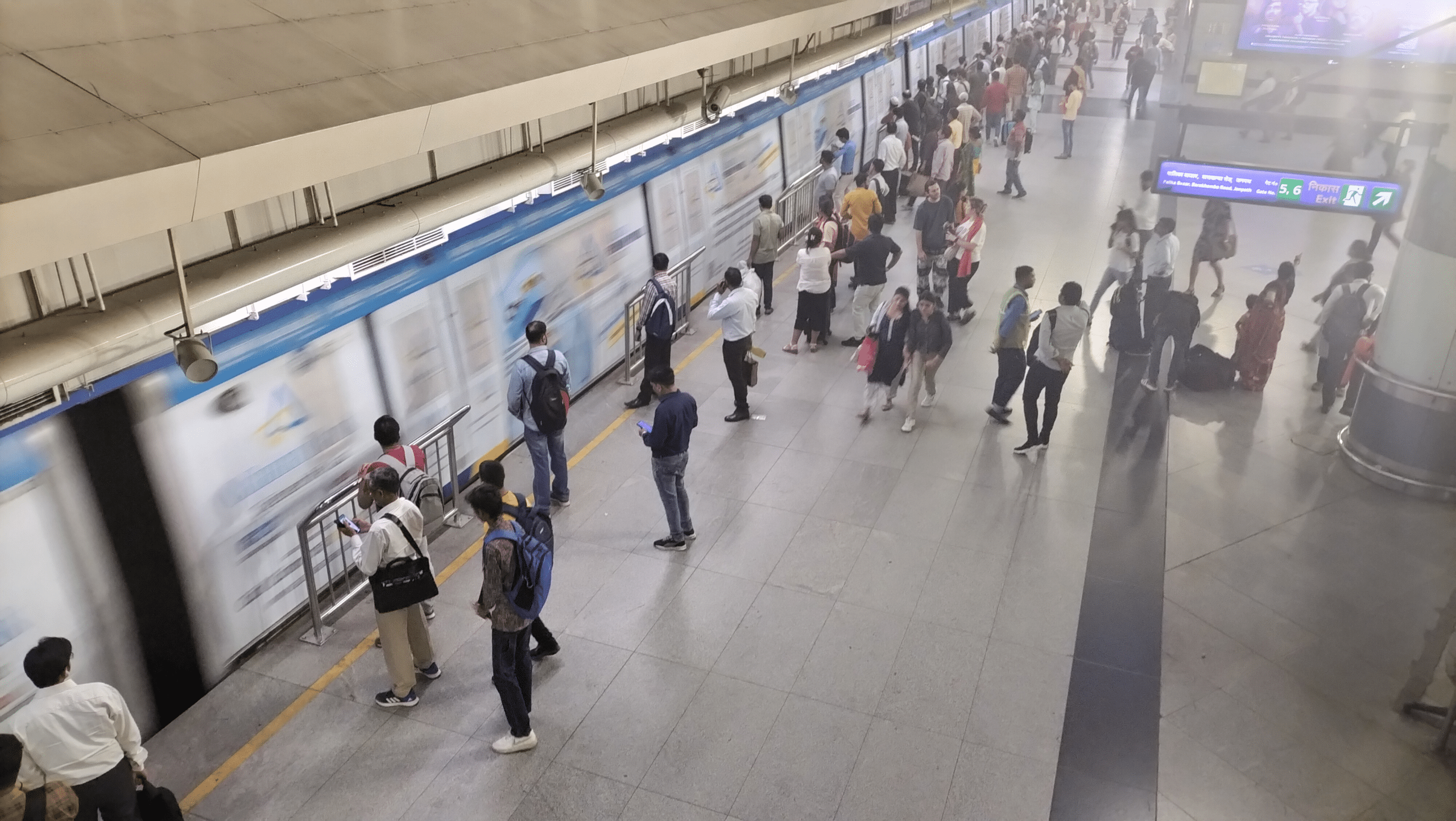

Overcrowding is also a pressing concern in India, with cities like Bengaluru operating a fleet of 6,500 buses for a population of 12 million, when the ideal fleet servicing this population should be 14,000 buses. While increased ridership can yield economic and educational advantages, it does not inherently enhance public transport quality or safety. Although the presence of more women in buses can contribute to a sense of security, issues such as harassment and disrespectful behavior from crew members persist. A survey of 500 women in Delhi revealed that 80% had encountered buses not stopping for them, while over 50% reported experiencing humiliating remarks from male passengers and crew members when boarding for free. Moreover, male passengers frequently decline to yield seats, even in designated female-only sections. Another survey, this time of 3,800 students at Delhi University, highlighted that women are willing to extend their travel time by 40% if it means a safer route. This points towards the importance of increasing safety on public transport in India – something that free tickets alone cannot guarantee.

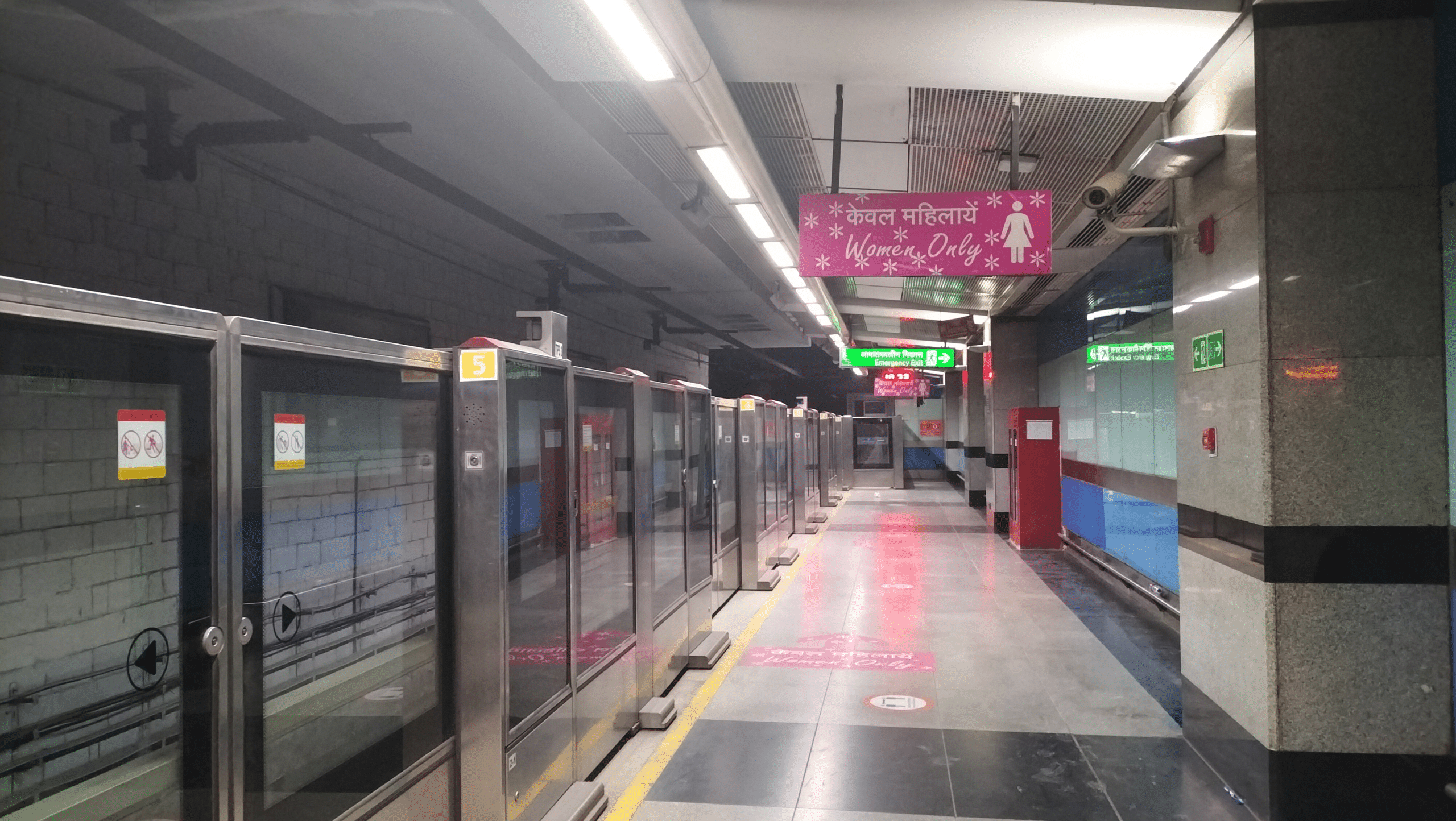

Offering a free bus service with the current fleet means that many areas remain underserved. Women from these areas may have to rely on shared autos or private buses instead. To address this, the bus fleet must be expanded, and service frequency improved. Additionally, investing in the overall quality of public transport – its frequency, reliability, safety, and accessibility – is crucial. It is also important to include more women and transgender people in the transport workforce, to create gender-friendly infrastructure systems, and to create a safe and accessible first and last mile.

Read more about gender-sensitive reforms in public transport in Kerala in this detailed case study.

Granting free access to buses to all residents presents challenges in monitoring the success of the scheme. In Telangana and Karnataka, women are encouraged to apply for smart cards, which would gather important data on female ridership on different routes at different times. This data can be used for improving accessibility, prioritizing infrastructure at stations, and planning buses that cater to journeys outside of peak hours. Eventually, they could develop into a national common mobility card. However, this complicates the scheme, and it can exclude marginalized women who may not want a smart card due to being undocumented or fearing more control from their husbands or male relatives. Introducing awareness campaigns to ensure that women are aware of the scheme and apply for the card are necessary measures. In Tamil Nadu, paperwork has been eliminated from the free bus ridership scheme to make it as accessible as possible.

A Simple And Quick Implementation So That Women Can Take The First Step

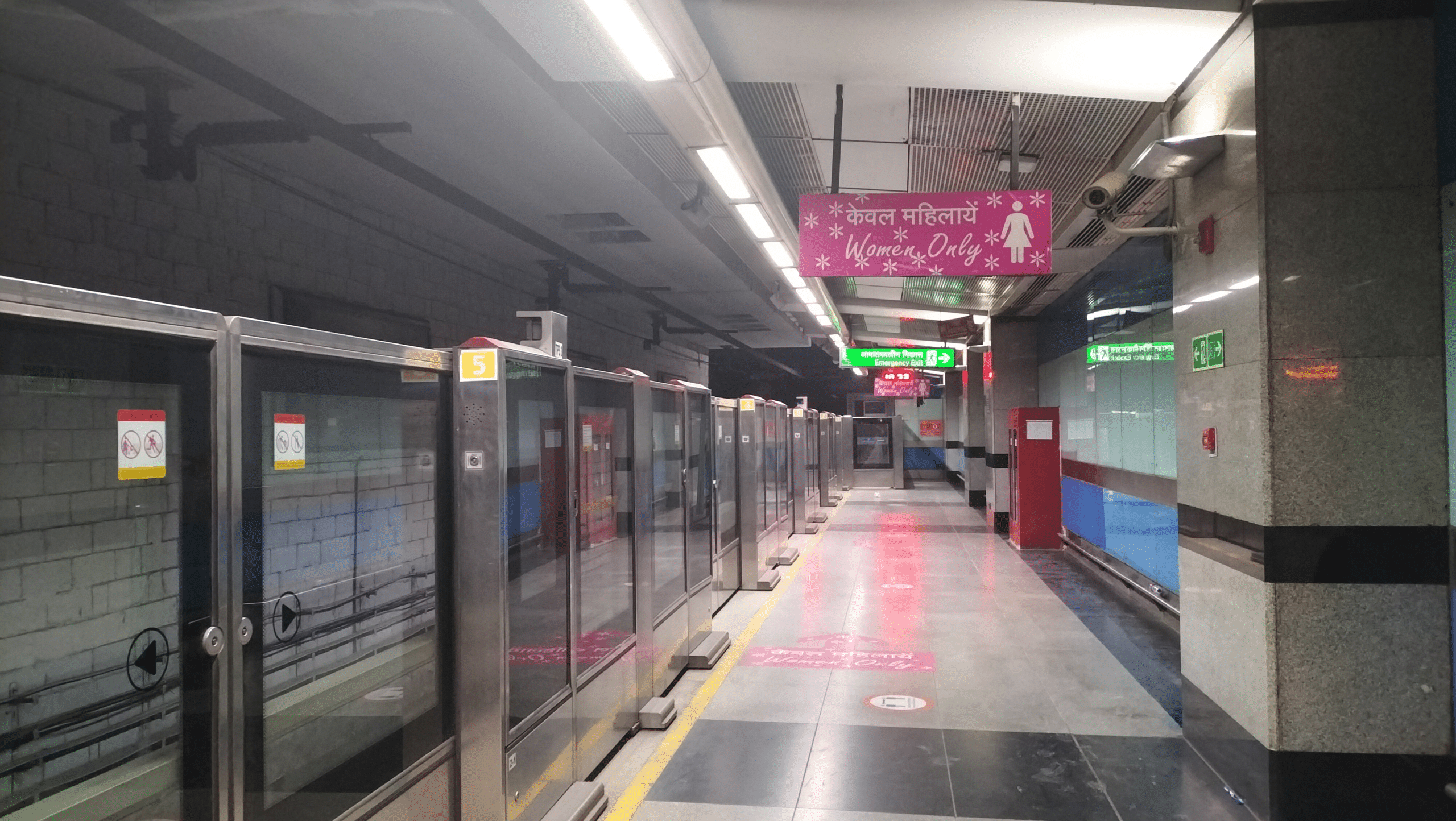

Despite its shortcomings, the Shakti scheme is an important step in empowering women in India to use public transport. While this kind of scheme enables women to access better educational, health and economic opportunities, it also results in mode shift from individual vehicles or 2-wheelers to public transport systems. The governments implementing it have said that they want to extend the scheme to further improve the freedom of mobility of women in the country. In Delhi, this might include free metro travel for women, an idea that has been heavily debated since 2020.

Importantly, visibility of women in public transport is growing, which can help to tackle safety concerns: The “safety in numbers” principle makes it much harder for perpetrators to harass or attack women. Combined with education and a cultural shift towards more respect for women on public transport and elsewhere, this is another component of women’s empowerment.

While the scheme reduces barriers to transport systems, transport planners need to assess the actual impact of the scheme on women of all skill and education levels. If the trips made by women are towards accessing educational or economic opportunities, or if the increased access to mobility creates additional care responsibilities. A detailed cost-benefit analysis estimating the direct benefits – including for example the improved labor force participation of women and the potential reductions in GHG emissions and congestion – should be undertaken to assess the actual impact of the scheme.

Ensuring the enduring impact of the Shakti scheme entails addressing remaining challenges. Financial aid from governments could alleviate revenue loss and mitigate criticism. Enhancing transport coverage and quality through investment would further support the appeal and accessibility of public transport. Exploring public-private partnerships offers promising avenues for funding and system improvement. Utilizing data on female ridership can inform infrastructure enhancements to foster a safer environment for women. In the realm of transport planning, gradual implementation is typical, requiring patience and ongoing assessment to improve the offer. Importantly, the simplicity and rapid implementation of the Shakti scheme has already led to significant results, empowering women to initiate change.