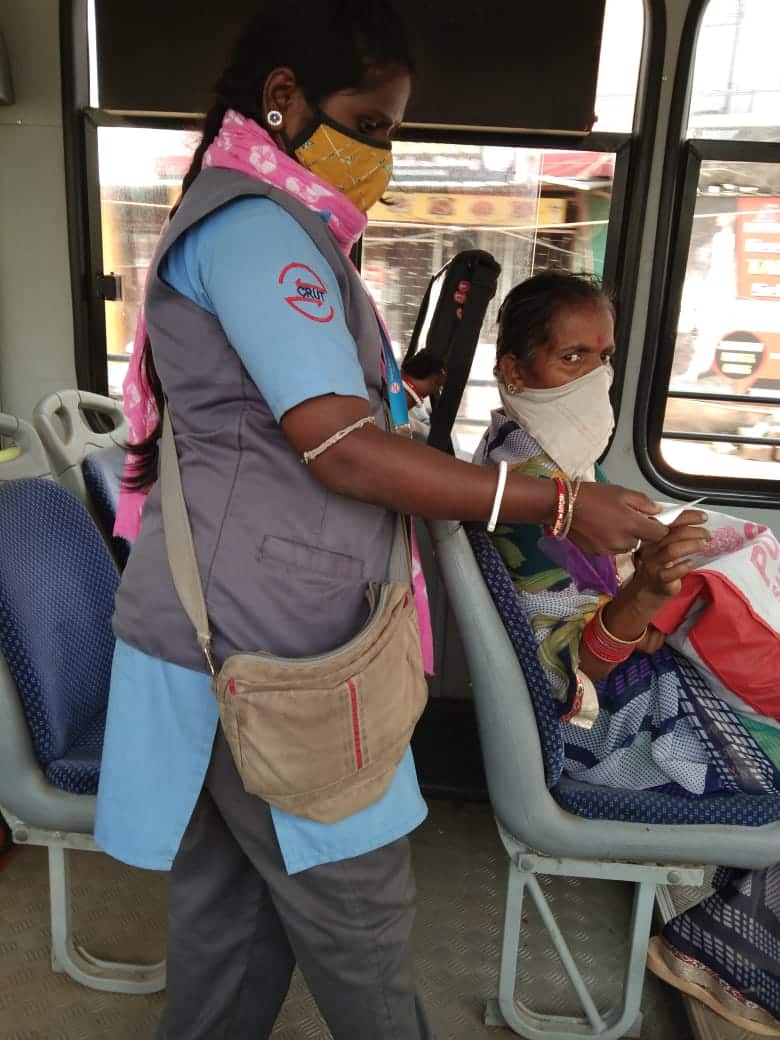

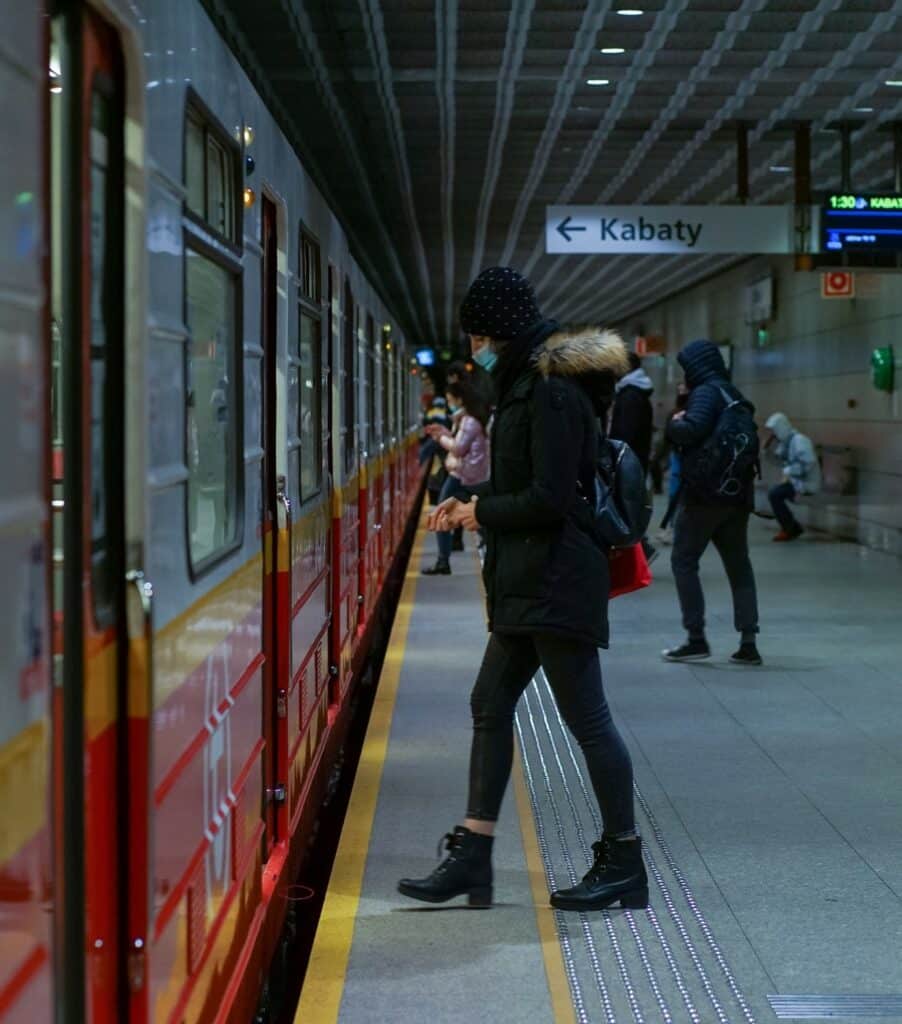

At this point in history, it is no secret that when moving in public spaces women experience high rates of sexual harassment. The personal accounts by women globally have led to the realisation that something needs to be done – at least among women’s organisations focused on improving the quality of the experience in the built environment for women and non-binary and transgender individuals.

By Melissa Bruntlett

In 2018, Women in Urbanism Aotearoa (WiU) joined the voices, creating a campaign to share the stories of women in New Zealand to try to educate the public on what it’s like to use public transport and walk and cycle as a woman in New Zealand. WiU co-founder Emma McInnes explains why the campaign was particularly important:

“The motivation came from hearing the stories of young Wāhine (women), and particularly from women of colour within WiU that were fed up with the level of sexual harassment on public transport.”

Addressing awareness to an often-invisible problem

Emma continues by identifying that she herself had been harassed many times on public transport, but recognizes it was probably not to the level that women from the rainbow community, women of colour, women living with disabilities, young women and teenagers were experiencing. She notes that for many women, the harassment, especially for these groups, can be very physical, very sexual in nature, and very intimidating and scary.

“There was a lot of anger and stress about how they were experiencing public transport, so we thought it would be good to call it out,” says Emma

“What they really said to us was, if you’re a woman of colour, not only do you experience sexual harassment, but you also experience racism, so you get hit with the stick twice.”

What WiU have been able to do with that is to take the stories to policy makers and politicians and it has been compelling for them.

“Reading those stories is really awful, and I kept thinking I must do something with them, and I’m not exactly sure I have the power to do something with them and people have given me their stories in a very trusting way. I’ve been using them in presentations and in conversation with decisions makers and powerful people.”

The campaign, featuring snapshots of stories from anonymous women accompanied by illustrations, help bring to light the very real and sometimes unbelievable experiences. The public response to the campaign, particularly from men, was shock. Emma revealed she received a number of messages from men who were outraged because they were convinced that if they saw this type of thing they would call it out. The reality is that these men were likely the few that would.

“Harassment can be invisible, and the campaign helped make them understand what they should be looking out for and that certain women experience it more.”

Filling the data gap

In addition to the campaign, WiU launched a survey to gather better data about the experience and prevalence of sexual harassment in public spaces.

“We wanted to work out if we could get a better understanding of what was happening and amplify those voices that weren’t being heard,” explains Emma.

Although the survey didn’t reach the groups they wanted to address, having mostly attracted responses from pākehā (white) women between 25-40 years old, the survey did provide valuable data that WiU could then use for further activities.

“What we did understand is that even from that group of cis pākehā women we were able to see that over 70% had been harassed in public spaces, on public transport, walking and cycling, at some point.”

The role of advocacy in data collection

The question is, should data collection be the responsibility of advocacy groups like WiU? With less resources in time, money and people, this kind of work is quite intensive, but as Emma notes, sometimes it takes an advocacy group to make a safe space for people to be willing to share their experiences and answer surveys of this kind. Many women, but especially women of colour, women with disabilities, those in the rainbow community or otherwise, have a certain level of distrust in transport authorities, local police and/or local government. Often women don’t feel safe enough to report incidents of sexual harassment, fearing they’ll not be heard or that even if they are, nothing will be done to address it. These concerns are only compounded by the reality that data collection from public agencies frequently do not record concerns of personal safety, or when they do, the data is so low they don’t know what to do with it.

“As an advocacy organization, WiU has the strength to run a campaign to say what we need to say and be very bold about it,” Emma explains.

Through their work, WiU has been able to get media coverage about the topic, continuing to be interviewed about their campaign and survey even four years later. For Emma, WiU is a better place to come and talk about these issues, and as a result they have been more successful because they’re being more intentional about it.

Still, Emma is quick to emphasize that This kind of intentional work shouldn’t always fall on the shoulders of advocacy.

“WiU has to try to fill the gap however we can,” she says, “But organizations in New Zealand [and globally] that do data collection need to realize how important this information is and do the research without having to be asked.”

She affirms that as women working in the industry as planners and designers, WiU happy to help assist with the framing of the questions and talking about the gaps in the knowledge or the questions we need answered. However, there’s a real part to play in the industry to help organisations like WiU and others around the world to do better quality data collection, because it shouldn’t just be advocacy groups doing this kind of work all the time.

The ongoing journey to creating safer, equitable public spaces

Following the initial survey in 2018, Emma and her colleagues at WiU recognized that while the data collected was helpful in launching conversations with Auckland Transport, New Zealand Transport Authority, and local Councils to address the issues identified, it didn’t meet their wishes in capturing the experiences of non-cis-white women.

“Going back and reflecting we now realize that there are lots of gaps and questions that were raised that we’d like to address now,” she explains. “WiU is predominantly white, so we’re probably more likely to get feedback from those of women. It’s our journey to recognize this and diversify, to be better and do better, which will probably help give us richer data and responses. This will help our surveys, and more importantly, ultimately help more women.”

Emma notes that since the initial survey, a lot has changed culturally that may encourage people to respond differently to an updated survey, particularly, as it relates to women with disabilities. While the first survey was launched simply to get some initial data to work with, WiU is keen to do it again and see if they have a better reached. Observationally people appear to be more comfortable now talking about whether they have a disability or not, according to Emma. In 2018, respondents could have been hard of hearing or have ADHD and they weren’t checking that off in the survey.

“Those are very much things that make you experience the urban environment different from the way other people experience them.”

“Since 2018, because of social movements and how our environments are changing, how people are changing and societal changes people probably have a greater awareness about how that effects their experience their urban environment,” Emma explains, “and how the urban environment can make public transport, walking cycling and public spaces safer for people who are hard of hearing, blind, or living on the spectrum or with a mental illness.”

This greater awareness could lead to better results, and WiU hopes a new survey would reach a more diverse audience and be more detailed to drill down to where people are coming from, answering questions like:

“Is it inner city buses that are the problem or more outlying areas?” and “Who lives in those communities?”

Having a more diverse and detailed understanding of the challenges can help create more concrete solutions.

To explore further city initiatives and campaigns against sexual harassment on public transport, read our blog on ‘Safe commuting for all – How cities can tackle sexual harassment on public transport’.